As more borrowers take out high debt-to-income loans, regulators are stepping in to cool the housing market – but many in the industry are warning of unintended consequences

There are fears that some borrowers may be locked out of the housing market as a result of APRA’s recent changes to the minimum interest rate buff er. The regulator stepped in in response to rising house prices and high levels of borrower debt.

Banks are now expected to assess a borrower’s ability to service a loan from 3% above the loan product rate, up from 2.5%.

House prices have risen more than 18% over the last year, with some cities and regional areas seeing even larger jumps. Part of the reason for this price growth has been record-low interest rates, which are making larger loans more affordable.

Twenty-two per cent of new home buyers are now borrowing more than six times their income, up from 16% of buyers a year ago.

In making the announcement, APRA chair Wayne Byres said the action had been taken to ensure that banks were lending to borrowers who could afford the level of debt they were taking on, “both today and into the future”.

Byres said it was expected that housing credit growth would run ahead of household income growth in the period ahead, and while the economy was expected to bounce back as lockdowns were lifted across the country, the balance of risks warranted stronger serviceability standards.

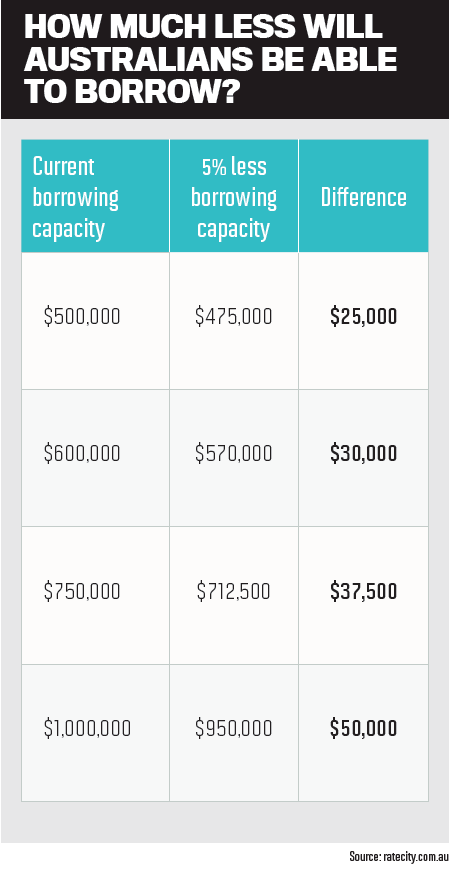

APRA expects that the increased loan serviceability buff er will reduce maximum borrowing capacity for the typical borrower by around 5%.

In its analysis, ratecity.com.au said a household that under the old rules could borrow a maximum of $500,000 would see their borrowing capacity fall to $475,000 – a drop of $25,000.

Research director Sally Tindall said many borrowers didn’t borrow at full capacity, but anyone planning to do so would need to reassess their budget.

“These new changes will clip the wings of people borrowing at their capacity,” she said.

Although the changes were designed to protect people from taking on risky levels of debt, she warned they would hurt first home buyers who typically had smaller incomes and deposits.

“This change will be a hard pill for some borrowers to swallow; however, it will ultimately protect them from overstretching themselves, and that’s a good thing.”

Accusing APRA of completely disregarding regional Australia, Cairns mortgage broker Roger Ward said the change could spell disaster for regional economies around the country. The interest rate buff er increase has been implemented nationwide, but Ward said the need to cool the housing bubble was a “capital city issue”.

In fact, Ward said housing affordability was very good in places like Cairns, where you could still buy a property for $400,000, which meant that single-income families could enter the market.

“With all the concerns the Reserve Bank and APRA have about market velocity and housing affordability, this simply does not apply to most of regional Australia,” he said.

Regional Australia has done it tough over the past 18 months. Thanks to COVID-19, tourism in places like Cairns has really suffered. With record-low tourism numbers, Ward is seeing businesses in severe distress as they rely on local visitors to survive.

The construction industry is managing to slightly off set the economic suffering, but Ward believes APRA’s changes will impact that also. He has seen this happen before and knows the consequences all too well.

“Macroprudential reforms have been used before, most famously in the previous investor boom in Sydney and Melbourne,” he said.

“In this case, higher deposit requirements and higher interest rates were used to curb the hyper-stimulated investor market. This, too, was applied nationally and suppressed investor activity throughout regional Australia which had nothing to do with the capital city investor boom.

“Places like Port Douglas, where almost 50% of housing stock is owned by investors, suffered from this policy, and the irony was that this area needed policy support, not oppression, at the time.”

Ward said APRA could use a postcode-based lending policy to prevent the banks from applying the criteria to regional areas, and thus assist with regional recovery.

“If APRA had been serious, they could have applied this on a postcode basis, and then we could concentrate on problem suburbs,” he said.

“Then you could leave the other postcodes out of it and allow them to continue the recovery from the devastation of COVID.”

As a mortgage broker who assists women who are recovering from financially abusive relationships, Ward fears that single-parent families and those on low-to-moderate incomes will be the most affected.

“When you’re a woman recovering from a broken relationship, 99% of the time you have still got the kids and you’re trying to do this on a single income, and for those women the servicing has gone up by another half a per cent,” he said.

“It’s the ones at the bottom end that are going to be locked out.”