Iain Hopkins explores how creativity can be funneled into innovative outcomes for business

Iain Hopkins asks where our childhood creativity goes and how we can bring it back

Innovation can come from anyone, anywhere – that’s because all human beings are creative. We lose sight of that fact as we progress from childhood through to adulthood and it gets buried, especially when we hit the workforce. Yet there are countless examples of everyday workers using creative thinking to resolve business issues.

The three biggest innovations at McDonald’s came from people who were flipping burgers. The Big Mac, the Egg McMuffin and the Filet-o-Fish all came from the front line, not the head offi ce. The worker who invented the Filet-o-Fish realised that Catholics would not eat hamburgers on Fridays. He suggested an alternative might be a burger containing fish. The idea went up the chain, and a new product line was born.

“Ideas come from where problems exist,” suggests Jason Clarke, founder and lead ‘mind worker’ at Minds at Work. “Go where the problems are. You need to empower people where the problem is and say to them, ‘What would you like to do about this?’ ”

TOP TIPS

1. Define what innovation means to your organisation.

2. Ensure members of your executive team understand and are aligned in terms of what good innovation looks like for your business.

3. Engage your broader leadership group to think-tank innovative concepts regularly, and build a bottom-up culture of idea generation.

4. Leverage your strategy teams and business experts to work with your high-potential leaders to turn concepts into strong business cases.

5. Prioritise practical, ROI-focused ideas and gain executive agreement on value-based investing.

6. Create a culture that supports the continual flow of new ideas and strong feedback loops.

2. Ensure members of your executive team understand and are aligned in terms of what good innovation looks like for your business.

3. Engage your broader leadership group to think-tank innovative concepts regularly, and build a bottom-up culture of idea generation.

4. Leverage your strategy teams and business experts to work with your high-potential leaders to turn concepts into strong business cases.

5. Prioritise practical, ROI-focused ideas and gain executive agreement on value-based investing.

6. Create a culture that supports the continual flow of new ideas and strong feedback loops.

Creativity and innovation

First, it’s important to recognise the close, interconnected realms of creativity and innovation. Clarke suggests the relationship is similar to the one between bread and toast; in other words, the two are one and the same.

“Creativity is one of the fundamental mindsets you need – you cannot have innovation without creativity. Innovation is simply when you say, ‘Let’s take those ideas and turn them into things which will deliver outcomes or progress or whatever else’. Innovation is the application of creativity.”

Clarke confirms that everyone is born creative, but this particular trait “goes into hiding” as we get older. “If you think about people who are anxious, they are actually expressing creativity; they are imagining something that might not be a problem. People who dream – dreams are creativity while you’re asleep. It’s there. Our ability to invent and create is hardwired into us – you can’t stop it.”

Even empathy, he notes, is a form of creativity. Whenever we’ve felt for someone or wondered how it would be to be someone else, we have been using our imagination and creativity.

So, what happens to that creativity?

“I think part of the problem is people aren’t given the confidence to be creative,” Clarke says. “A lot of that happens in early childhood. It’s a bit like sport. When kids are encouraged to be sporty when they are little, they become comfortable with that as part of their personality. But if you’re one of those kids who was never picked at sport, you tune that part of you out.”

What goes wrong?

Most businesses, consciously or not, then proceed to squash that creativity even further. But it must be remembered that, like McDonald’s, creativity can actually be used to enhance and improve business outcomes. It’s just a matter of drawing it out of people.

“Organisations will ask, ‘Have you got any ideas?’ People will generate ideas and the organisation will say, ‘That doesn’t address any of the problems we’re dealing with. I was hoping someone would come up with an idea to solve problem F, not A, B, C’,” Clarke says.

The first step is to identify whatever the organisation is not happy with, something that isn’t working as best it could. It could be a loss of market share, or bad customer experiences, or too much time being wasted in meetings. Once the problem is established, it’s time to tap into the minds of employees.

“This is where creativity becomes innovation – it becomes targeted. Very often the creativity doesn’t have a target,” Clarke says.

The concept of the ‘lightning rod’ is handy to keep in mind. The problem with the traditional ‘ideas box’ is that people will submit ideas but very few can actually be used. A lightning rod, on the other hand, is staked to the ground to bring sparks to where you want them.

“Organisations should say, ‘Let’s have a dozen suggestion boxes. Suggestion box one is how do we improve the customer experience? Box two is how do we cut our operating costs? Box three is how can we boost staff morale? So the ideas are going into something useful,” says Clarke.

To cite just one example, on 25 May 1961 President John F. Kennedy announced before a special joint session of Congress the ambitious goal of sending an American safely to the moon before the end of the decade. He didn’t specify how it should be done, but he planted the seed.

The announcement kick-started a period of incredible invention and innovation – people had a clear goal to work towards, and it would take their own creative ingenuity to make it happen.

Funnelling the ideas

A second key tip is to create some form of creativity process so the wonderful ideas have a direction and pathway to eventually end up as an innovative product, service or ‘thing’.

“The trick is making it simple and straight enough so that ideas can actually get up,” says Clarke. “You can get people fired up about creativity and innovation – that’s very easy. People are waiting for someone to invite them to have this discussion. So it’s about getting on a train, filling it up with coal, and getting people really excited. But if there’s no track for the train, it will just plough into the dirt. No one knows what happens next.”

The alternative is that there are tracks, but they run like the roller coaster at Disneyland: complicated, twisty, double-backing.

Clarke cites a recent client that had an innovation process in place, but it was so long, with many layers and steps, because it had been put together by the legal department and the finance department and the rest, to ensure nothing dangerous or risky happened.

“All they succeeded in guaranteeing is that nothing ever happens,” he comments. “Waiting years for approval is just going to kill everyone’s enthusiasm.”

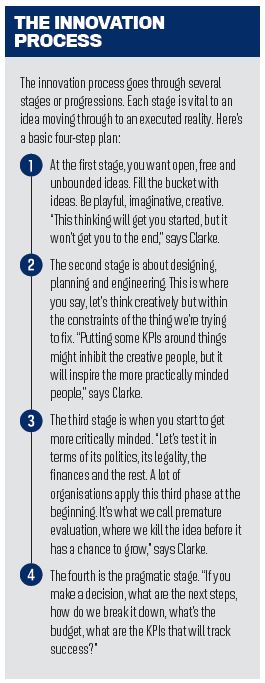

Each of those stages requires different thinking. You start off naive, then you become more practical, then critical, then pragmatic. You may need different people at different stages. “This means that, if I say to John, ‘You’ve got this great idea; you’re now in charge of making the whole thing work’, it will probably fail – we don’t have the mindset that can do all of those things. I don’t think anyone does. We say to clients: great minds don’t think alike – you need a diverse set of characters, skills and egos to do it all,” Clarke says.

Importantly, innovation needs cynicism as much as it needs optimism. It isn’t just about believing in things and hoping for the best; you need someone to say, “Is this really going to work?”

“However, if you get the sequence wrong, if you are negative too early, or optimistic too late, it won’t happen,” Clarke warns.

Further tips

There are two further critical pieces to consider: organisational culture, and the role of leaders. Clarke notes that clients often approach him and talk about their fear of failure, yet this is not a human condition. When a child walks for the first time, they are not afraid to fall.

“What we’re afraid of is blame and ridicule,” Clarke says. “We’re afraid of being accused of screwing up. It’s not the failure that we have a problem with; it’s the way people respond to us having tried to do something new and it didn’t go exactly the way we thought it would.”

Clarke’s recommendation to organisations is to get past the narrow definition of ‘failure’.

“We use the word failure to describe a range of things. Let’s imagine I’m a pilot and I didn’t put the wheels down when I landed the plane because I was too busy texting. That’s a failure, a potentially very serious failure. We shouldn’t be using the same words when describing, ‘Well, John wanted to try something new and it didn’t work quite the way we thought it would work’. I don’t think John should be punished for trying something new, because he could potentially figure out the way forward for the rest of us.”

The most important contribution leaders can make is their influence on culture, one that fosters innovation. A leader’s job is not necessarily to be the innovator – you don’t have to be the genius; you have to find the genius. Richard Branson is the prime example of this. Virgin consists of around 250 companies. Branson didn’t come up with every single idea within those companies. But he’ll be the guy who had the idea, or the guy who supports the guy who had the idea, or the guy who turns up at the launch and makes a big fuss about the guy who had the great idea. He’s quite happy to put his ego aside and step back and let other people step forward.

“That’s the hardest challenge for leaders – they get excited about being a leader and their egos get too big. If you’re a boss with 1,600 brains working for you, you’re just another one. Get out of the way and encourage people to put their ideas forward,” Clarke says.

No time? No excuse

Not surprisingly, Clarke scoffs at the suggestion that there is no time to be innovative today, to take the time to think outside the accepted square. He flips this concept on its head: Why are we so busy in the first place? Why are we working so hard? The answer is simple: the old ideas don’t work anymore.

Yet the whole idea of innovation is not to invent new work. It’s to simplify and make better use of our resources.

“We invented the wheel not to make ourselves busy but because we couldn’t be bothered walking,” says Clarke. “The commute time in Sydney is, on average, 15 hours per week. At what point do we say, ‘OK, this is ridiculous. We need to find a better way. Could we work from home? Could we use flexi-days or alternate start/finish work times?’ I don’t buy the idea we don’t have time – the time we have is going into old ideas that don’t work anymore.”