Consumers are increasingly concerned about where their money’s going, and you should be too.

No doubt most readers of this magazine would dub themselves ‘ethical’; we do our jobs properly and put the interests of the customer first.

But ethical finance means something quite different – it’s about really noticing where your clients’ repayments are ending up.

Supporting charities

Lenders and brokers getting involved in good causes is nothing new. Homeloans Ltd recently announced support for the ‘Buying Time’ breast cancer campaign, and a number of the large banks pledged sums for disaster relief in cyclone-hit Vanuatu. But proving consistent charitable aims over the lifetime of a loan – which could be decades – is more difficult in a charitable environment of constantly changing fashions.

Perhaps ethical finance lies in ownership and corporate governance, rather than charitable initiatives. Credit unions would argue they’ve been doing ‘ethical finance’ at a local level for years, and furthermore, because they’re owned by their members, they need to appear responsive, unlike larger companies dealing with anonymous profit-focused shareholders. Of course, credit unions still finance a tiny fraction of loans and thus have limited influence.

Divestment

‘Divestment’, ie ending investment in certain companies, is becoming a “global trend”, according to Shane Oliver, head of investment strategy at AMP Capital Market. He told the ABC that divestment was “a choice, and the choice is along the lines that fossil fuel is dangerous to the environment, causing global warming in the longer term”.

In the UK the Guardian newspaper, which also operates in Australia, has called for two major charitable foundations to pull their money out of fossil-fuel companies, and the Bank of England has warned about the dangers that “investments in fossil fuels … may take a huge hit” because of regulations. Back in Australia, the University of Sydney declared in February that fossil fuel divestment would play a role in reducing its carbon footprint.

Lenders and brokers

Some lenders have proactively changed their investment criteria. Bendigo and Adelaide Bank doesn’t lend to companies that focus on exploration, mining, manufacture or export of thermal coal or coal seam gas, according to third party general manager Damian Percy. “We have found over recent times that our position on environmental sustainability resonates with many customers and, unsurprisingly, brokers themselves. That is, they are concerned about the environment and are looking to take practical steps to minimise the harm they do or might indirectly facilitate.”

Some brokers have already integrated their ethical views into their business model. Future Home Loans, set up in March by Simon Sheikh and Adam Verwey, is a brokerage that uses only products from ‘fossil-free lenders’. The brokerage aims to show the major banks that their investments are losing them valuable business – and claim $15m has already been moved away from these institutions, in their three-month pilot.

Evidently, brokers are well positioned to guide clients towards ethical options. What has yet to be proved is whether ethical finance can provide a profitable niche for those brokers who put in the extra work to follow it.

Deciding who’s ethical

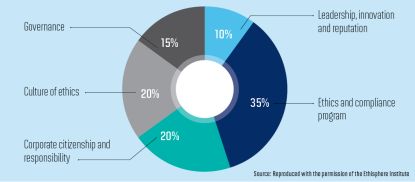

The Ethisphere Institute provides one way to 'measure' how ethical a lender is. The institute produces an annual list of the world's most ethical companies, which this year included both National Australia Bank and Teachers Mutual Bank. They use the following criteria:

Related articles:

Gaining respect gains business

How ‘friendly’ is your site?

Do you pass the Google test?