Homestart's CEO on how the government-backed lender is tackling SA's housing challenges, and why other states should follow its lead

Homestart's CEO on how the government-backed lender is tackling SA's housing challenges, and why other states should follow its lead

Whether you believe the housing market in Australia is ‘working’ depends largely on whether you’re on the ladder. In 2017, Australia’s state governments finally began listening to both sides. First home buyer grants returned to NSW and Melbourne in the form of stamp duty concessions, and FHB numbers increased by a third nationwide to a five-year high.

The problem is, so have property prices. The typical repayment requires 36% of an average family’s income in NSW and 32% in Victoria, and most first home buyers earn far less. As banks move away from high-LVR lending, or demand substantial lenders mortgage insurance payments, the upfront costs of buying remain daunting and, for many, out of reach.

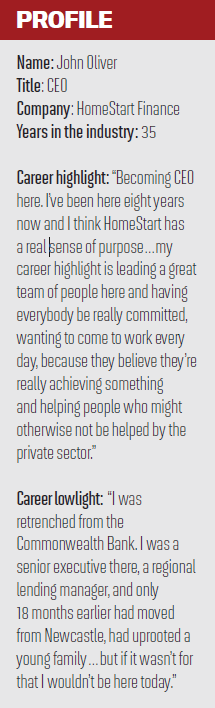

In South Australia they do things differently. In 1989, SA first home buyers also faced intimidating obstacles, recalls HomeStart CEO John Oliver. “That was a time when interest rates were pretty much at their peak and home ownership was very much a challenge,” he says. The SA Government’s solution was to set up its own lender for those who couldn’t get a loan anywhere else, with a simple objective: “We’re here to give people a hand up, rather than a handout”.

Products with a difference

While the name HomeStart rings few bells outside SA, it is an expanding presence in the broker channel, which accounted for 43% of new HomeStart lending in 2016/17. “Our relationship with brokers is a strong one,”

Oliver explains. “It’s a complex one, because the product we’re dealing with is slightly different to the typical loan out there in the market.”

HomeStart’s clients will be familiar to brokers: they are first home buyers with limited savings, and divorcees with limited incomes. There is no upper income limit, but Oliver is specific about the bank’s target clients: “If you can get your home loan through a bank, go there; you don’t need us.”

For many brokers, the loans HomeStart offers may seem unusual. To begin with, the upfront costs are much lower: for graduates they will lend up to 97% LVR, with a loan provisioning charge instead of LMI, of around $1,425 for a 95% LVR loan.

“The thing that disappoints me is that other state governments don’t come and look at the HomeStart model and replicate that – because it can be replicated”

Oliver sees this charge as a major point of difference. “Lenders mortgage insurance, depending on the loan amount, could be anything from $8,000 upwards,” he says.

For repayments, HomeStart takes a percentage of the borrower’s net income, indexed to CPI. Therefore CPI and the loan term, rather than interest rates, determine a borrower’s repayments. This also means that repayments can go up in a year when other bank-borrowers’ repayments go down.

With borrowers having the ability to get a loan from around $5,000 upfront, Oliver doesn’t believe HomeStart needs to offer guarantor loans. “I’m not a big fan of mum and dad providing guarantees; I think there are considerable risks in that,” Oliver says. “Not only do parents need to assume risks, but the other reality is the relationships might not last the distance.”

Could HomeStart’s model go national?

In the current debate on housing affordability, government-backed lenders have barely been mentioned. Labor proposes cuts to negative gearing, while Liberals favour building more affordable rental housing.

As Oliver explains, government-backed lenders are subject to various constraints. “Governments aren’t meant to compete with the private sector or to run commercial operations that have a competitive advantage competing with the private sector,” he says. HomeStart is forced to pay back funds to the SA Government to ensure its interest rates aren’t undercutting commercial lenders.

HomeStart is not subject to APRA, although Oliver says he tries to stay in line with its directives. “Where I want to be as a CEO is that, if APRA walked in the door today, we would pass their inspection from all of the underlying governance principles that they’re looking for.” With HomeStart supervised by ASIC and under the NCCP, Oliver says, “there are a lot of people who look at us to make sure we play with a straight bat”.

Currently, HomeStart has just one equivalent: KeyStart, the West Australian lender, although KeyStart has less independence from government.

“Western Australia and South Australia have shown that it can be done and it can be done quite responsibly,” Oliver says. He claims that applying the model to NSW and Victoria could increase home ownership by 6% in the former and 8% in the latter.

“We’ve been profitable for over 28 years, and we’ve returned over $560m to the state government”

A number of trends suggest the HomeStart approach to lending could spread. In October, small business ombudsman Kate Carnell suggested the government should set up a taxpayer-backed bank for unsecured small business lending, similar to the UK’s British Business Bank.

Concurrently, the Productivity Commission is investigating competition in the financial system and could recommend major changes in its final report in July.

Helpfully, the east coast state governments have money to spend, due to huge stamp duty receipts: the NSW State Government’s surplus for 2016/17 was $5.7bn. Oliver recalls that HomeStart was set up – albeit in 1989 prices – for around $3m.

HomeStart’s difficulty, but also its strength, is that its approach to lending is almost incomparable to that of its rivals. Not only are its upfront costs and repayments calculated differently, but the end goal is quite different: as brokers and banks chase ‘lifetime’ customers, HomeStart wants a customer for just five to six years.

“We do nothing to retain customers here. For every customer that moves to a mainstream financial institution, we pop the cork on some champagne,” Oliver says. “We say we’ve done our job.”