Shocking new ABS data shows how your clients are getting slugged

As the cost of a roof over one’s head continues to outpace the capacity of many Australians to pay for it, a parallel surge in property taxation is quietly reshaping the nation’s fiscal landscape — and fuelling a political reckoning ahead of the May 3 federal election.

Figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics show that property taxes continue to become an increasingly important — and controversial — source of government revenue. With states banking on booming housing markets to patch budget holes, Australians now contribute an average of $29,751 each in total taxes to federal, state and local governments. Of that, a growing slice is coming from levies on land, property transfers, and investment holdings.

In Victoria, where the state Labor government has raised property taxes on investors and tightened payroll levies, the average resident paid $6348 in state taxes — the highest in the country. That’s a 9.5 per cent jump in just one year. The state now generates a greater share of its income from property-based taxes than any other in the federation.

Yet this rising revenue comes at a time when many residents feel more financially precarious than ever.

A nation on the edge of housing stress

Australia’s housing affordability crisis has deepened into a structural problem years in the making. Home prices across Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth have surged over 70 per cent in five years. In Sydney, the median price hit A$1.19 million in March. In some cases, even mould-ridden homes requiring A$600,000 in repairs are fetching close to A$3 million at auction.

The disconnect between income and shelter costs is stark. While property values nationwide have climbed 40 per cent in five years, inflation-adjusted household incomes have edged up just 13 per cent.

It now takes the average buyer about a decade to save for a 20 per cent deposit. And in nearly one-third of all electorates, at least 33 per cent of households are in mortgage or rental stress — where monthly expenses outstrip earnings — according to Digital Finance Analytics.

Indeed, renters are bearing the brunt of these levies indirectly. Landlords facing higher tax bills frequently pass them on through increased rents — further fuelling affordability pressures in a rental market where vacancy rates have plunged to just 1.3 per cent.

Governments banking on the boom

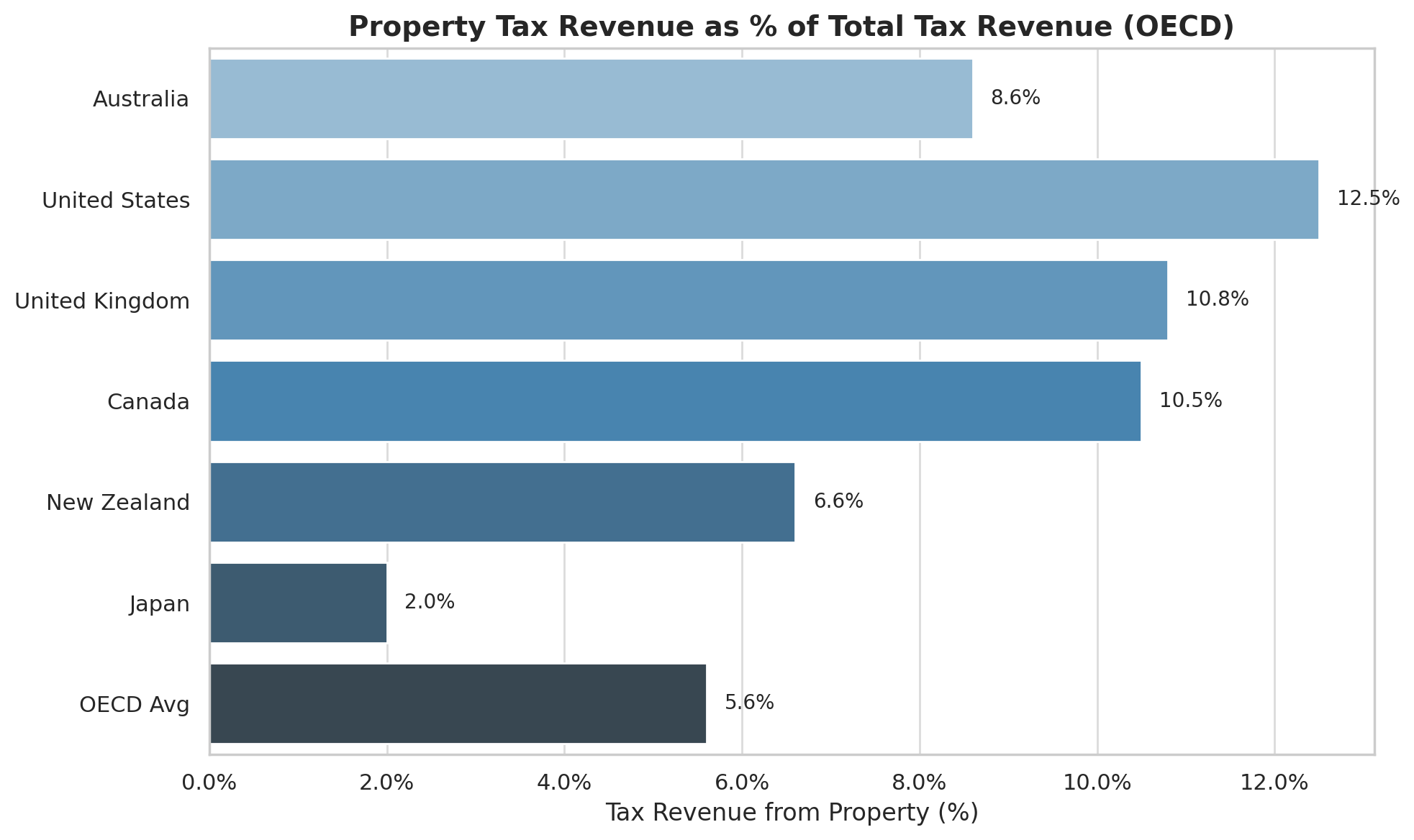

Tax receipts from property have become an essential funding mechanism for cash-strapped state governments, particularly in Victoria and New South Wales. In total, property tax revenue accounted for a significant share of the record $802 billion in combined government tax intake last year.

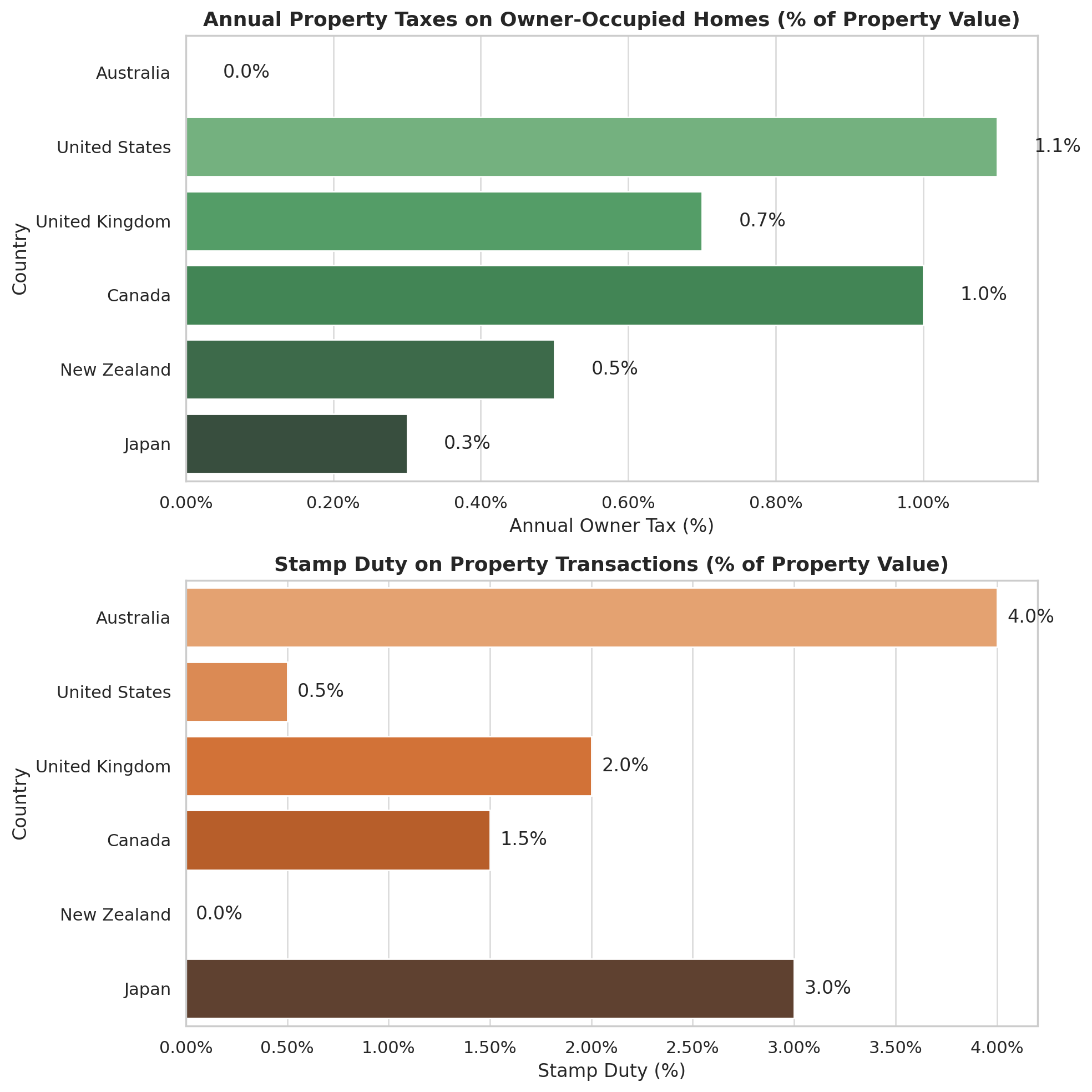

Unlike income or corporate taxes, property levies offer a dependable stream tied to asset values. As housing prices skyrocket, so too do the collections from stamp duty, land tax and investment property surcharges.

“Property taxes are politically easier than income tax hikes,” said one tax expert. “But they’re also regressive when applied without restraint — renters and lower-income earners end up absorbing more of the burden than the headline figures suggest.”

That sentiment echoes the OECD’s long-standing warning: Australia’s tax system over-relies on personal and corporate income, while under-utilising more equitable, growth-friendly taxes such as consumption and land levies.

Yet, paradoxically, it is the politically untouchable structure of the property tax system — especially generous concessions for investors — that many economists argue is exacerbating the problem.

A tax system that encourages speculation

Australia’s unique tax treatment of investment properties — notably negative gearing and the capital gains discount — is seen as a key driver of housing unaffordability. Investors can deduct rental losses from other income, and enjoy a 50 per cent discount on capital gains if they hold the property for more than a year.

Combined, these incentives fuel speculative activity that bids up prices while doing little to stimulate new housing supply.

Currently, nearly 2.3 million Australians declare rental income — roughly 15 per cent of the taxpaying population, up from just over 1 million at the turn of the century.

Reform remains elusive. Labor’s Bill Shorten proposed winding back negative gearing in 2019 and lost the election in a landslide. Since then, the major parties have steered clear of revisiting the issue, even as housing affordability worsens.

Electoral consequences looming

Housing — and the taxes surrounding it — are front and centre in the current campaign. Labor has pledged to build 1.2 million homes by 2029, expand shared-equity and guarantee schemes, and spend $10 billion to fund new stock for first-home buyers.

The Coalition, meanwhile, is promising tax deductions on mortgage interest, access to superannuation savings for deposits, and a $5 billion infrastructure fund to support housing development.

But voters remain sceptical.

In key marginal seats where affordability has eroded most — such as Watson, Blaxland, and Bradfield — Millennials and Gen Z voters are deserting the major parties in droves. Many are disillusioned not only by their dim prospects of home ownership but by the perception that governments are profiting from their pain.

The way forward

The Reserve Bank’s pandemic-era interest rate cuts, followed by 10 successive hikes, triggered a housing rollercoaster that exposed the fragility of the market — and of the tax settings underpinning it.

Analysts agree that without a broader rebalancing of the tax mix — one that encourages home construction, discourages hoarding of multiple investment properties, and reduces the cost barriers for first-time buyers — the cycle of rising prices and rising taxes will continue.

Have something to say about this story? Let us know in the comments below.