Will the tax cuts fuel or curb inflation?

The National government has handed down Budget 2024 promising to curb cost-of-living pressures through tax cuts while keeping inflation at bay.

During the Financial Advice New Zealand webinar, Bring in the Experts: Post Budget Webinar – Economic and Consumer Impacts, ANZ senior economist Miles Workman (pictured above) discussed the implications of the budget and what can be learned from the previous government’s policies.

Will the tax cuts fuel or curb inflation?

Perhaps the most contentious point of Budget 2024 was the impending tax cuts, as the government walks the balance of providing cost-of-living relief without it significantly adding to inflation.

Workman said the timing of the tax cuts, which are due to take place July 31, potentially could fuel spending growth in the near term, particularly given the high starting point of inflation.

“The first thing that the Reserve Bank is going to think is ‘crikey, that’s not very helpful’,” Workman said.

“That’s extra income for consumers and it does represent a small upside risk to near-term consumer spending, and therefore, inflation.”

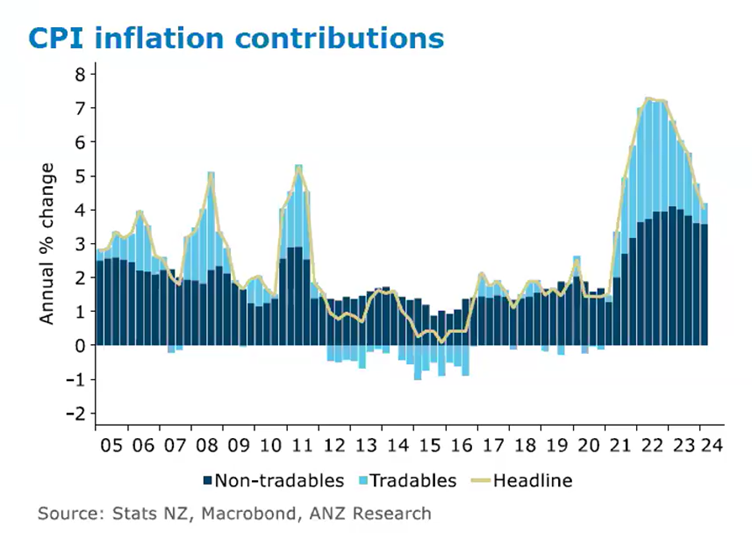

Therefore, ANZ expects inflation to rise by 2.8% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2024.

However, Workman said the income tax cuts on their own represent only around 0.5% of GDP in the year to June 2025, which is “more than offset by lower expenses”.

“If you think about Budget 2023, which was Labor's last budget, they increased spending by 1.4% of GDP with no offsets, and at the time inflation was running at about 6%,” he said.

“So, we’ve got a smaller impulse from tax cuts, but the tax cuts are offset by lower spending, and we got inflation at a lower starting point.”

Overall, operating policy changes, such as the tax and spending cuts, are expected to shave off around $5.5 billion over the next four years.

“Ultimately, it would be a pretty hard sell for the RBNZ to get super hawkish on the back of this budget given that they didn't get super hawkish on the back of 2023 budget… The disinflationary story is holding up.”

Won’t Kiwis just spend the money?

Workman said another thing to consider is where New Zealand is in the business cycle.

“Households who are receiving the tax relief, a lot of them are going to have a very high marginal propensity to consume basically meaning every dollar that goes in goes out because they are living week-to-week and paycheck-to-paycheck.”

However, he said there would be some households who, due to broader economic pessimism, would decide to save rather than go out and spend.

Another question is how are businesses going to respond?

The biggest problem for the RBNZ, and what is making inflation so sticky, is domestic inflation, which is driven by the labour market. However, Workman sees the effect on the tax cuts on businesses as a “small temporary bump”.

“Given the state of the economic downturn, the consumer pessimism, and households in belt-tightening mode, are businesses really going to hire more workers on the back of these tax cuts?

“I think the answer is probably not.”

On the other side of the equation, government spending is weighted heavily towards the labour market.

“If you are looking at it dollar-for-dollar, you could actually argue that the hit to employment would be harder and faster with lower government spending than any positive bump from tax cuts.”

Overall, while the RBNZ may be concerned about the near-term inflation risk, Workman said the composition of the government changes might suggest the medium-term inflation risks are mitigated by this budget.

“It suggests the Reserve Bank won’t be in a rush to cut the OCR anytime soon, but it also suggests they have a bit more confidence in the outlook going forward.”

The structural balance: Is the budget disinflationary or deflationary?

While the tax and spending cuts may be disinflationary, the government has also increased capital spending at a similar rate.

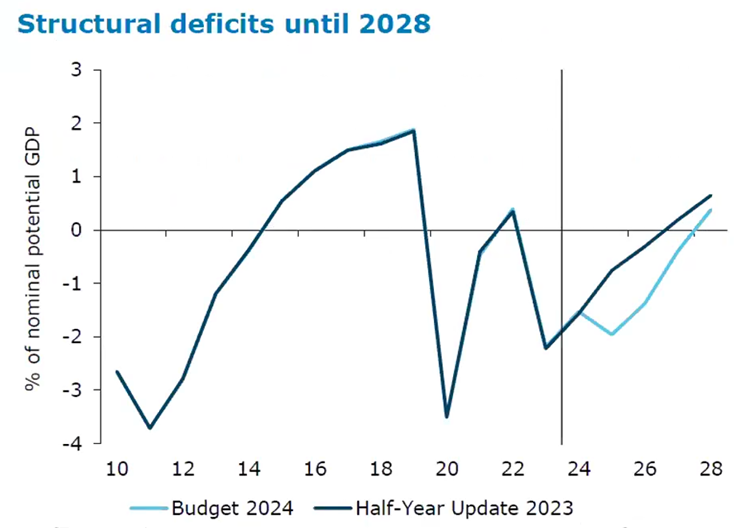

Workman said the overall fiscal settings are therefore “about par” with what was signalled during December’s half-year update, albeit with a different mix.

Is the budget disinflationary – where inflation is still positive but shrinking?

Workman said yes.

But is it also deflationary – where inflation is negative and falling?

“Well, that’s a different question altogether.”

Workman said it’s essential to look at the economy’s structural balance, an economic measure that calculates how much the government is taking out of the economy compared to putting in.

The important factor about the structural balance measure is that it removes impacts of the economic cycle and one-off shocks like earthquakes or cyclone Gabriel, for example.

“We’re running structural deficits all the way through to the year 2028. This ultimately means that the government is pumping more money into the economy than it is taking out until 2028,” Workman said.

“So, while we may have the fiscal settings that are consistent with a slowing positive inflation impulse, they are not outright contractionary until June 2028 where we’re running structural surpluses.”

Goldilocks and the NZ economy

A common critique of the previous government’s policy was that their fiscal settings were too hot for the economic conditions, and that drove inflation.

Equally, you could argue that the current government’s policies, which are pursuing fiscal consolidation during an economic downturn, could be too cold.

But unlike Goldilocks’ porridge, Workman said that nuance matters when it comes to the economy, and adjusting economic levers takes time to get it ‘just right’.

“The current downturn the economy is going through has been purposely manufactured by the Reserve Bank to tame inflation – the faster the fiscal consolidation, the sooner RBNZ can cut the OCR.”

Ultimately, the lesson of Goldilocks and the Three Bears – and the New Zealand economy – is that there is no such thing as a free lunch.

Workman said the impact of delivering an expansionary fiscal policy into an overheated economy has been significant:

- Crowded out private sector activity via a higher than otherwise OCR.

- Value of government spending eroded by inflation and inefficiencies.

- Not rebuilding fiscal buffers ahead of the next big shock.

- Fewer choices down the track to deal with long-run issues such as climate change and an aging population.

“It’s certainly overdue that fiscal consolidation happens. When you think about the interaction between fiscal and monetary policy, I think the upshot is the Reserve Bank can have a bit more confidence that fiscal policy is going to be a better ally going forward.”