Is this the perfect storm?

Many, many years ago my wife-to-be worked as an estate agent.

She sold mortgages that were backed by an exotic device called an endowment policy. Rather than paying down the mortgage, the payments went to an endowment policy that was cleverly supposed to accumulate so much by investing that it would happily pay off your mortgage at the end of the term and, who knows, probably even give you a tidy lump sum as well.

Well, as any of you who are old enough to remember them know, endowments didn’t end well. Enthusiastic salespeople made big claims and, at least in my case, the policy didn’t actually gain enough to pay off the house.

But that’s a little beside the point, because what was also happening was that the property market was going NUTS. Estate agents sporting mobile phones that looked like briefcases were desperately hunting for new properties to photograph and stick in their shopfronts. The idea wasn’t to give sellers a realistic valuation – say anything just to get the stock in. Prices were going up so fast that someone would definitely pay the valuation if not this afternoon, next week for sure.

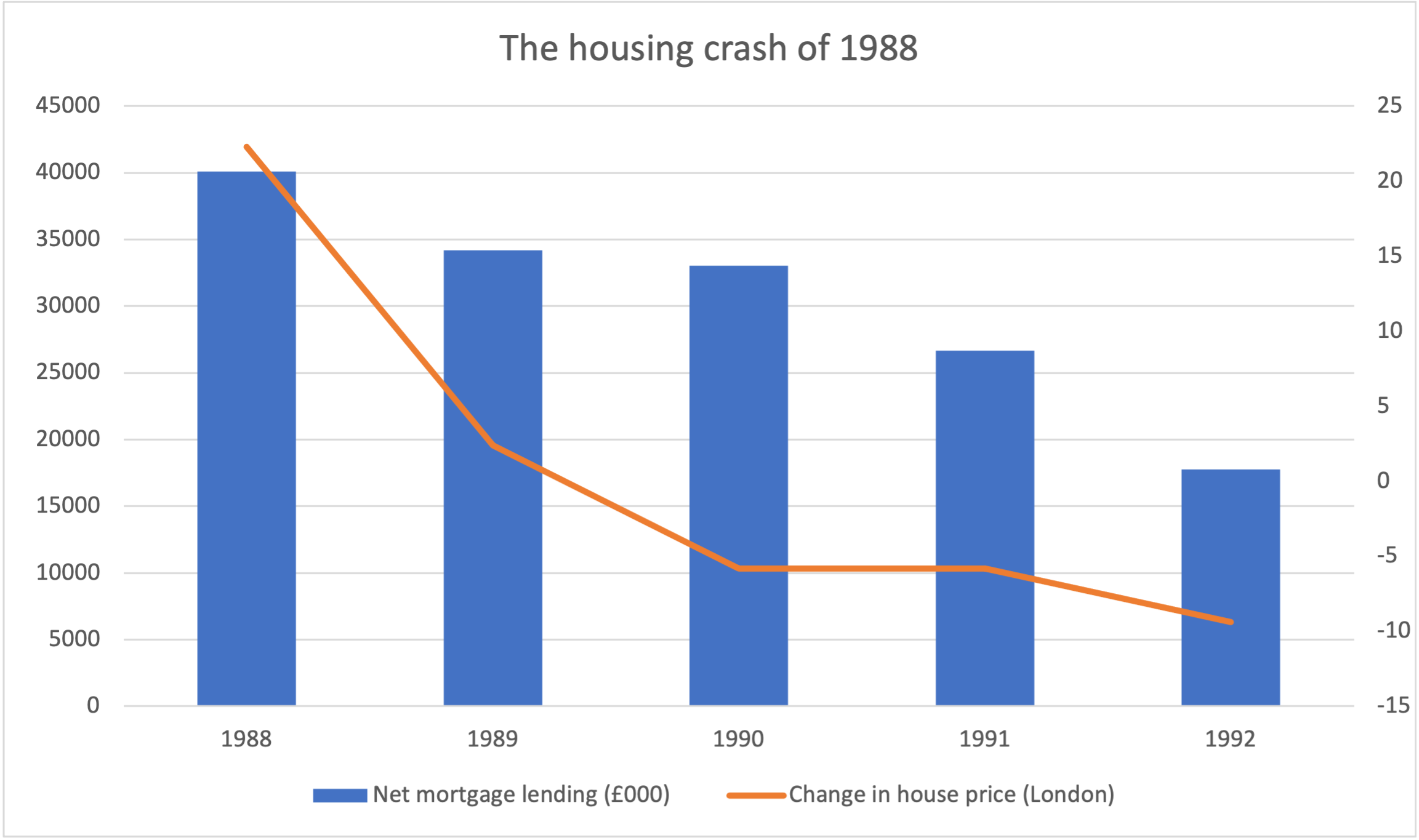

Financial pressure (from a falling stockmarket) caused the government to cut interest rates, and house prices continued to surge. Then, the following year, rates started to rise again to try to stop the runaway market, and, in August of that year, the government stopped double tax relief on mortgage interest available to couples.

The ensuing rush to buy before the deadline added fuel to the super-hot market until, in early August, it was like someone had flicked a switch. Instead of desperately hunting for houses to sell, the office my wife worked at was turning them away, and trying to get vendors to list at prices that might possibly get a sale. At a lot less than they had hoped for, and maybe not for years.

But that was 1988, when earnings to house price ratio maxed out at 4.25. The figure now? Around 9.1 times.

The latest figures from Nationwide now show that property prices rose at 14.3% for the year to February – that’s the fastest pace for 17 years.

“A combination of robust demand and limited stock of homes on the market has kept upward pressure on prices,” said Robert Gardner, Nationwide’s chief economist. And that is, in Nationwide’s words, “a surprising amount of momentum given the mounting pressure on household budgets and the steady rise in borrowing costs.”

And worryingly enough, mortgage approvals are falling. Bank of England data released on Tuesday shows they fell to 71,000, down from January’s 73,800. Forecasts were expecting the February figures to hit 74,850.

Net borrowing slipped to £4.7 billion – it was £5.9 billion the month before.

Which means that economists are concerned. “The acceleration in house price growth will add to concerns that the pandemic housing market boom is getting out of hand,” Andrew Wishart, senior property economist at Capital Economics told Reuters.

“March is probably the peak of the boom”, agreed Gabriella Dickens, senior UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics when speaking to Yahoo news.

So is the sky going to fall?

Well, there’s never a 100% answer (don’t put it down in writing where someone can find it 10 years later and say AHA – look what an idiot YOU are) but that having been said, there is a lot of pressure on the market now.

House prices are outstripping wage growth in 90% of the country, so, according to ONS figures, affordability has become worse in 300 of 331 local authority areas. (Not you, City of London and Westminster. In Westminster, for example, the price to average earnings ratio has actually dropped, plummeting to a mere 18.9 times from 2020’s 25 times)

But – and there is a big one – there are a number of other factors in play that could help soften the blow.

High demand is still continuing to help prices stay up – plenty of people still want homes.

New homes are more expensive – COVID supply chain and shortage issues are driving up the price of materials. “Consumers have not been put off by energy costs rising, rates ticking up and costs rising elsewhere. Talk to housebuilders in the last two weeks and the biggest question is ‘can we get the materials?’, not ‘can we pass on the costs?” Glynis Johnson, an analyst at Jefferies, told the Financial Times.

A wave of borrowers may return for a mortgage next year – nearly 600,000 people remortgaged in 2018 ahead of a rate rise and many of those were in a five-year fixed product – that could expire in 2023

So there you are, you see. I didn’t actually say that prices were going to fall, but if they do, I told you so.