Are we approaching a time when more fundamental reform of property taxation is needed?

The Council of Mortgage Lenders' senior economist Mohammad Jamei asks 'is it's time to reform stamp duty?'

Stamp duty is one of the biggest upfront expenses when buying a home, whether you are a first-time buyer or a home mover. The scale of this upfront charge can make the difference between prospective buyers going ahead with their purchase, or staying put.

The CML, as well as others such as the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), have long argued that stamp duty is damaging to the housing market and depresses activity.

Stamp duty is a transaction tax and so relies on people moving homes to produce revenue. But what if, because of the large upfront costs of moving, people don’t move? Perhaps they look at an alternative, such as building an extension instead. Then, revenues from the tax fall.

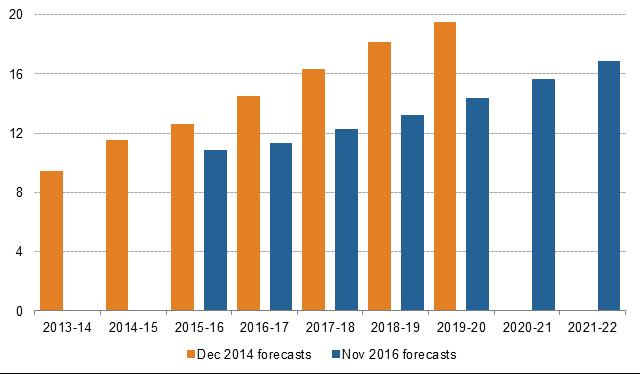

This is exactly what has happened over the past few years. Successive Budgets and Autumn Statements have revised down forecasts for stamp duty receiptsbecause property transactions have been subdued.

Tax and transactions

More recently, the downward revisions have been due not only to lower overall activity, but alsoto a stamp duty reform introduced in December 2014. This increased the tax bill for more expensive properties and has materially slowed down activity at the top end of the market, leading to a fall in the average value of transactions.

The reform also changed the structure of stamp duty, moving it from a slab system to a marginal one. But this has been criticised as only a slight improvement on what existed before, as the typical saving made on stamp duty was very modest.

Now, that’s not to say that stamp duty is the only factor affecting activity levels. Economic conditions, the availability of mortgage credit, house-building and house price inflation all affect transactions, too.

But, to give an idea of the scale of these downward revisions, stamp duty was predicted in December 2014 to bring in £19.5 billion a year in revenue by 2019-20, more than double the revenue at the time the forecast was made.

Propertysurcharge

Inits latest set of forecasts, published in November 2016, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) now expects £14.3 billion in revenue in 2019-20. Cumulatively, the downward revision in receipts over the five-year period from 2015-16 to 2019-20 comes to just over £19 billion.

This is despite a new 3% stamp duty surcharge on second homes – introduced in April 2016 – which has helped boost stamp duty receipts by 75% more than was originally expected.

Chart 1: OBR forecasts for stamp duty receipts

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility

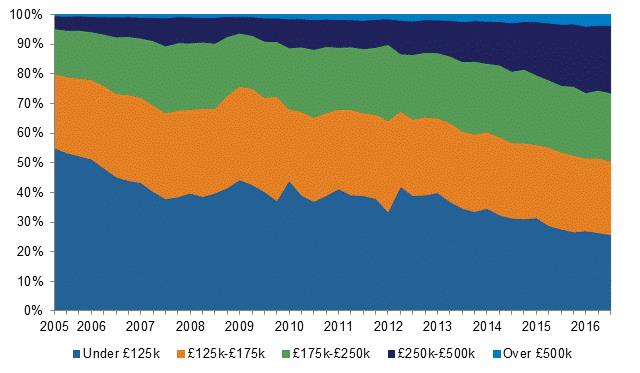

Fiscal drag has also managed to widen the tax base for stamp duty substantially. The thresholds have remained pretty much unchanged since March 2005, with the exception of a temporary respite during the financial crisis. Unchanged thresholds, coupled with rising house prices, mean more transactions are subject to tax, and toprogressively higher rates of tax, as they cross over the stationary thresholds.

This is put into sharp relief by looking back to 2005, a time when most first-time buyers could expect to pay no stamp duty at all. Fast forward to today and nearly three-quarters of first-time buyers pay stamp duty.

Chart 2: Property valuations for house purchases by first-time buyers, as % of all loans

Source: CML Regulated Mortgage Survey

Harder to move

The consequences of lower activity levels in the housing market affect more than just the amount of revenue for the government.

A low number of transactions reinforces inefficient use of housing stock. Young people find it harder to buy their first home; those in the middle struggle to trade up; and elderly people find it harder to move to homes more suited to their needs, or to unlock their housing wealth.

Then, there is the impact that lower transactions have on the wider economy. Low rates of mobility in the labour force mean that we have a less than optimal labour market, as workers are not able to move to where jobs are located, hindering economic growth.

The negative effect of low transactions should not be under-estimated. But it is also understandably difficult for a government that is trying to balance the books to overhaul a policy which brings in a sizeable amount of revenue each year.

Removing pinch points

It is clear that the modest reform in stamp duty in 2014 did not have a big impact. It effectively smoothed out pinch points in the old system but provided buyers with only a small saving. There were also unintended consequences, focused largely at the top end of the market.

For anyone interested in reading more on the taxation of housing, I would recommend chapter eight of the Mirrlees review, published in 2010, which discusses the subject in some depth.

More recently, the Redfern reviewadvocates taking a long-term view of the housing market and adopting a strategy that can be supported by successive policymakers. But while there have been numerous policies on the supply of housing, there have been no major discussions of the taxation of housing in my lifetime, apart from the Mirrlees review.

So, it begs the question: are we approaching a time when more fundamental reform of property taxation is needed?