Will we get busy soon? Apparently so…

Back in the 1980s mortgage lending boomed. Net mortgage lending rose from £7.3 billion in 1980 to £40 billion in 1988 – but that’s when the party suddenly started getting messy. There were many reasons why - but in August of that year, it was like a tap was turned off as estate agents scrambled to get sellers to drop prices while inventory soared – a complete volte face from just weeks earlier when they fought to get listings at any price. One of those reasons was a deadline for getting double tax relief for couples when buying a property together.

And why should we even care? That was when there were leggings and shoulder pads, housing affordability issues made the headlines and interest rates were high. But wait! Something similar could be about to happen, and there is a prediction that we should have some sunshine to make hay in soon – even if we have to wait a few days to let all the Reeves budget uncertainties pass.

Read more: Borrowing costs rise as Reeves budget fears spread

Online platform Rightmove says that we should brace for a surge in demand for smaller properties as some landlords begin to sell off their investments. This follows growing speculation that the current temporary stamp duty relief for first-time buyers may end in April next year.

Reports suggest that the stamp duty threshold for first-time buyers could drop from £425,000 to £300,000. If this change takes effect, buyers purchasing homes at the average UK price of £370,759 would face a stamp duty bill of £3,538 from March 2025, whereas they currently pay nothing under the existing rules – and this could well create a rush of people trying to buy before then, a small scale rerun of 1988.

Read more: Selling 'frenzy' as property investors try to avoid Labour tax grab

Rightmove’s Tim Bannister weighed in, saying: “The rumours that ‘nil rate’ and first-time buyer stamp duty thresholds will indeed be reverting to previous levels as of March 2025, rather than be held at their current rates, will no doubt be seen as an unwelcome additional cost by many buyers looking to make their move in 2025 – and potentially to those currently in the process.”

The general stamp duty exemption for home movers is also expected to drop from £250,000 to £125,000, potentially adding as much as £2,500 in extra tax for buyers purchasing above the new threshold. Bannister highlights how these changes could significantly impact first-time buyers, noting that under the current £425,000 threshold, around 58% of available homes are exempt from the tax. If the limit drops to £300,000, only 37% of properties would remain stamp duty-free—a decline of 21%, with the reduction likely to affect buyers in high-cost areas such as London and the South East.

Bannister expects an uptick in market activity before the changes take effect, as buyers rush to avoid the higher costs. "This could result in a busier Christmas and New Year period," he suggests, with the market scrambling to finalize deals ahead of the deadline.

Currently, the average property transaction takes about 152 days from offer acceptance to completion. With the Chancellor’s Budget scheduled for October 30 and the new stamp duty rules set to begin March 31, 2025, buyers who enter the market after the Budget announcement may struggle to close their deals in time unless all parties involved accelerate the process.

Boom to bust – the 80s housing crash

The UK experienced a significant housing boom from 1985 to 1988, driven by strong economic performance, declining unemployment, rising disposable income, and falling interest rates. During this period, GDP grew by more than 20%, and real personal disposable income increased by 22%. Mortgage lending surged from £14 billion in 1983 to £40 billion in 1988, and house prices rose rapidly, particularly between 1986 and 1988.

The boom was also influenced by deregulation in the financial markets, with banks entering the mortgage market, breaking the dominance of building societies. This competition encouraged easier lending practices, and mortgage rates became more aligned with market conditions, promoting further borrowing.

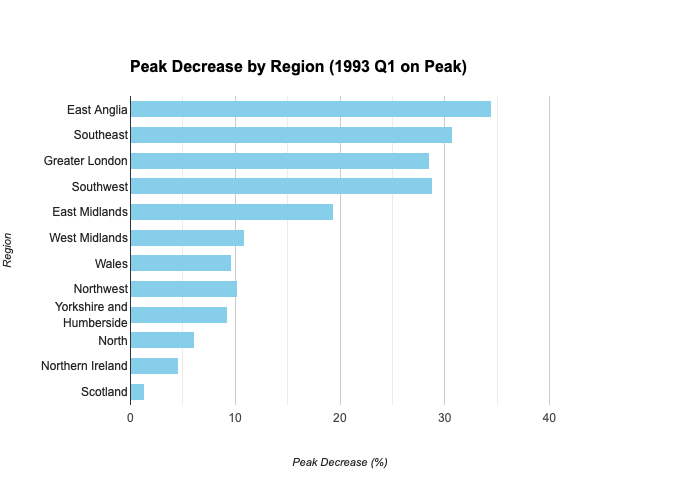

Where the late 80s crash hit hardest

However, signs of a market peak emerged in 1987 with a stock market crash and rising inflation. Although the government temporarily lowered interest rates to stimulate the economy, the market began to overheat. A key moment came in March 1988 when tax relief on joint mortgages was announced as ending, prompting a surge in transactions before the deadline.

By late 1988, the housing market had reached its peak, and economic conditions began to shift. Interest rates rose again, increasing borrowing costs. Mortgage lending and property transactions declined sharply, marking the start of the downturn. By 1989, house prices began to fall, and regional variations emerged, with prices in areas like London and the South East dropping the most.

The downturn continued into the early 1990s, characterised by rising unemployment, declining transactions, and a drop in house prices by around 30% in some regions. The concept of negative equity—where homeowners owed more on their mortgages than their properties were worth—became a growing issue, further exacerbating the housing market slump. This downturn, though severe, resulted in smaller overall price declines compared to the crash of the 1970s.