Treasury analysis predicts up to 2.5% increase

Capital gains tax increases to batter property investors. Government borrowing to drive up mortgage rates. Owners rushing to sell properties.

The property market does look like it could be thawing, but (and it’s a big but) there are some commentators who think that this bounce could be a dead cat bounce if the new government stuffs up their first budget next month.

In preparation for her upcoming Budget, Rachel Reeves is considering a significant increase in government borrowing, a move that could potentially drive up mortgage rates, according to official Treasury analysis.

Reeves is planning to do so by changing the rules that set how much the government is allowed to borrow and could ‘release’ up to £50 billion. The modelling suggests that changes to Britain's fiscal rules, as proposed by the Chancellor, might increase the cost of borrowing for both consumers and businesses.

The official Treasury paper highlights that even a small “fiscal loosening”(borrowing in layman’s terms) of just one percent of GDP could trigger a rise in interest rates of up to 1.25 percentage points. Furthermore, each £25 billion increase in annual borrowing could cause interest rates to climb by between 0.5 and 1.25 percentage points. This analysis is particularly relevant as Reeves is expected to ease borrowing rules in the October 30 Budget, potentially unlocking as much as that £50 billion we mentioned earlier for government spending.

Read more: CGT take soars even before potential rate hike

The research, published last December under the title The Impact of Borrowing on Interest Rates, reflects the Treasury's current thinking.

This comes at a time when mortgage rates, which had been cooling, saw some deals drop below 4 percent for the first time in months, and some economists predicting a return to 2.75% in the relatively near future.

Read more: Rates set to fall to 2.75% says major lender

However, with central interest rates currently standing at 5 percent, any increase at all would slug mortgage holders.

Former Chancellor Jeremy Hunt weighed in over the weekend, emphasising the long-term impact of higher borrowing on mortgage rates. He remarked, "The consistent advice I received from Treasury officials was always that increasing borrowing meant interest rates would be higher for longer – and punish families with mortgages.

“That would be a hammer blow and lead to mortgage misery for many people just at the moment the Bank of England is expected to bring interest rates back down.”

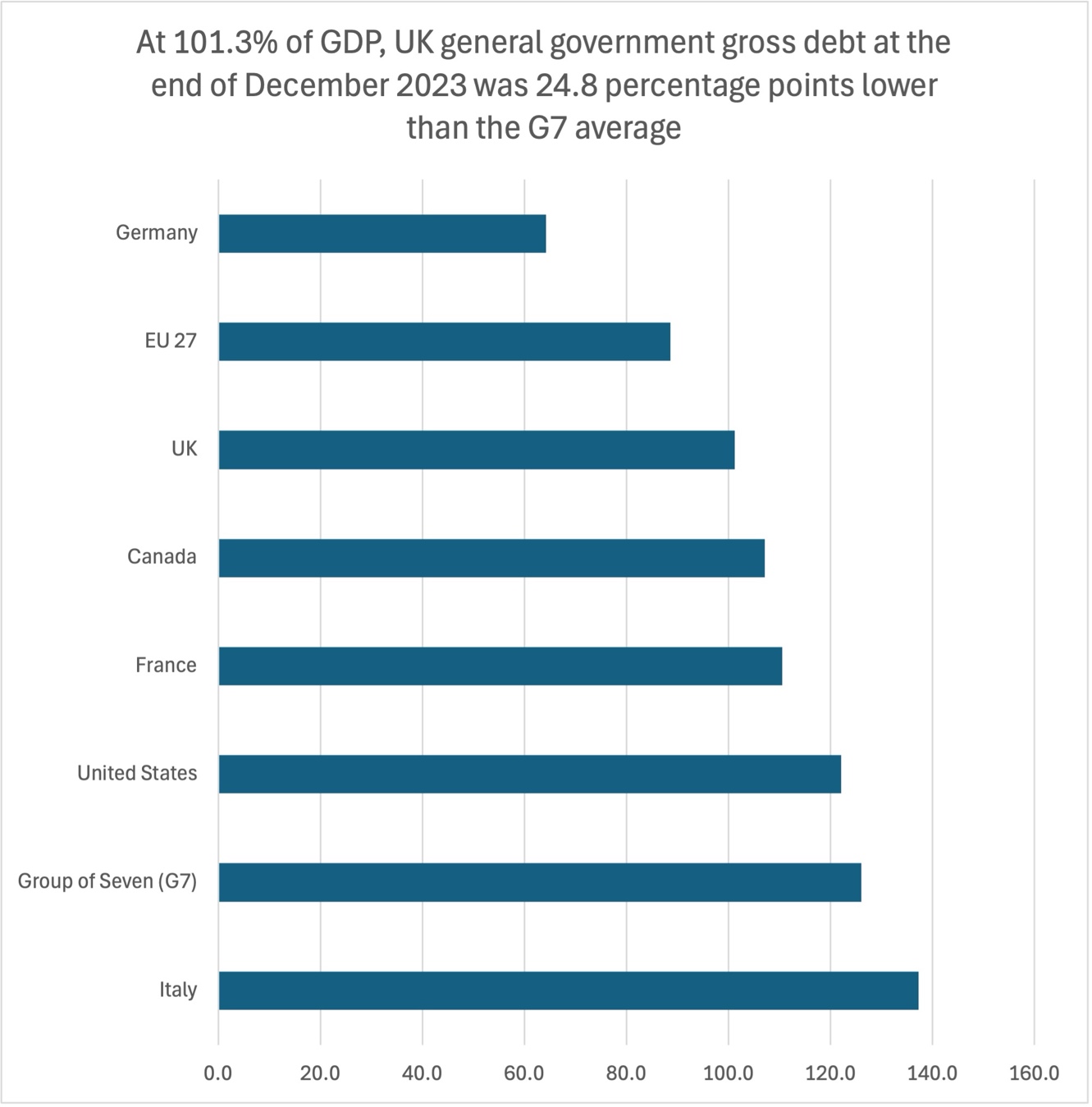

Hunt has called for the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) to be mandated to publish a full assessment of any changes to fiscal rules, especially as Britain’s debt has risen to 100 percent of GDP, a level not seen since the 1960s.

The consistent advice I received from Treasury officials was always that increasing borrowing meant interest rates would be higher for longer – and punish families with mortgages. https://t.co/CvpSxfeLkg

— Jeremy Hunt (@Jeremy_Hunt) October 6, 2024

Despite warnings, Reeves hinted strongly that she intends to move forward with increased borrowing to finance a large-scale capital investment program. “Invest, invest, invest” was her rallying cry, signalling a firm commitment to boosting government spending.

This move aligns with Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer's previous warning that the party’s first Budget would be “painful” and could involve tax increases to address a £22 billion deficit in public finances.

Some analysts have already suggested that the effects of additional borrowing may have been partially factored into current market conditions. For example, the yield on 10-year government bonds was 4.13 percent as of last Friday, reflecting investor concerns about the likelihood of more borrowing under Reeves' leadership.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) also expressed concern, labelling Reeves’s plan as "opportunistic" and warning that any relaxation of fiscal rules could lead to further increases in interest rates.

The IFS has been vocal about the potential risks. Carl Emmerson, its deputy director, told The Telegraph, “If you borrow a lot you are taking more of a risk that interest rates will be higher in response.” He emphasised that higher borrowing, particularly if used for current spending rather than capital investment, could push up inflation and compel the Bank of England to raise interest rates further.

However, the IFS also noted that borrowing for investment, rather than consumption, could stimulate economic growth if managed properly. “If you make some investments that perhaps encourage the private sector to invest, improve the growth rate and increase the capacity of the economy to produce, you then won’t have the Bank of England’s concern that it is inflationary,” Emmerson explained.

The Treasury paper similarly acknowledged that the impact on interest rates could be mitigated if the spending generated significant “supply-side benefits.”

Nevertheless, the Treasury cautioned that unanticipated increases in government spending, or tax reductions funded by additional borrowing, could stoke inflationary pressures and lead the Bank of England to raise interest rates in response. A spokesperson for the department emphasised that “the relationship between fiscal plans, inflation, and interest rates is complicated and can change significantly over time.”

The broader economic risks of increased borrowing remain a concern, especially as the UK’s debt levels have reached unprecedented heights. As Isabel Stockton, a senior economist at the IFS, pointed out, "It is crucial that the Government makes the case why these risks are worth taking, and how it will ensure the additional investment will be well spent."

What does The Impact of Borrowing on Interest Rates say?

For those of you who like technical financial speak - An unexpected increase in government spending or tax cuts funded by borrowing is likely to boost demand in the economy, which could lead to higher inflation. In response, central banks that target inflation, like the Bank of England, may increase interest rates. Economists have developed various methods to estimate how much interest rates could rise following additional government borrowing.

The Treasury has analysed this issue using the OBR’s simplified macroeconomic model, which focuses on four key variables: the output gap, inflation, the Bank Rate, and the nominal exchange rate. This approach assumes fiscal policy changes are unexpected, leading to a demand shock. According to their model, a 1% increase in GDP borrowing could raise interest rates by 60 basis points.

However, due to persistent inflation, economists suggest interest rates may now be more sensitive to demand shocks than before. By adjusting the Phillips curve to reflect the current economic situation, such as a tight labour market, estimates show that borrowing 1% of GDP could lead to a peak interest rate increase of up to 125 basis points.

Taking various models and recent economic factors into account, Treasury analysts propose that a 1% increase in GDP borrowing could push interest rates up by between 50 and 125 basis points, a range higher than most external estimates. External studies, like those from the IMF and OBR, also show that fiscal loosening can significantly impact inflation and interest rates, though the magnitude varies across regions and timeframes.

Picture: UK Parliament, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.