How a perfect storm of crises have worsened an already flawed housing market

Australians had to deal with one of the world’s least affordable rental markets even before they were simultaneously hit with a global pandemic, eight consecutive interest rate hikes, the highest inflation rate in 32 years, and some of the worst floods in the country’s history. Now, Australia is rapidly sinking into a homelessness crisis.

“We fear there is a tsunami of homelessness about to hit,” said Suzanne Hopman, the CEO of not-for-profit Dignity, which aims to support those experiencing and at risk of experiencing homelessness in Australia.

Hopman told Reuters Dignity was preparing for what could easily be the busiest Christmas the organisation had ever seen, as people continued to flock to its shelters for a safe place to rest, get food, and use other essential services.

Its shelter in Campbelltown was already packed to full capacity, it said.

SGS Economics and Planning recently published its rental affordability index. The report revealed a decline in rental affordability in every state capital city in Australia without exception, with most metropolitan areas requiring the average single pensioner or single, part-time working parent to spend at least 50% of their income on rent.

Hot off the press! The Rental Affordability Index is out now. Findings show rents are escalating faster than incomes across the country, with low vacancy rates, interstate migration and global supply chain issues contributing to increased rents. Read now: https://t.co/Bplb0BPOI9

— SGSEP (@SGSEcoandPlan) November 28, 2022

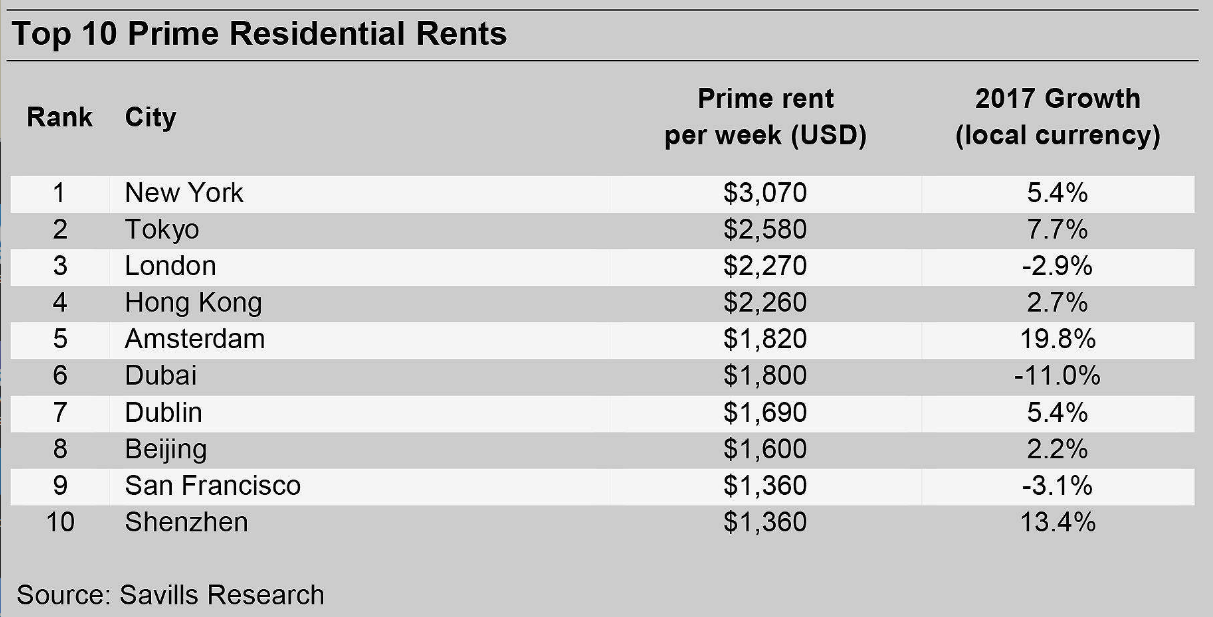

Savills has named Sydney the seventh most expensive rental market in the world, ranking above the bustling cities of Miami, Hong Kong, and Paris, while Demographia’s 2022 international housing affordability report ranked Sydney the world’s second least affordable market next only to Hong Kong.

Adding to the tsunami of homelessness and unaffordability is a dwindling rental supply. While rental stock is at a 20-year record low, more and more Australians are unable to afford a home post housing-price surge and are forced to look to rent.

“We have seen increasingly at the lower end of the market, people on lower income – the supply of rental stock available to them is reducing quite significantly,” said PropTrack’s director for economic research Cameron Cusher to Reuters. “[This] could have spill-over effects on homelessness.”

Borders reopening this year also meant migrant workers adding to the fierce competition for rent, and this competition in turn devolving into bidding wars. The NSW government had to announce a ban on auction-style rental bidding just last week.

Read more: NSW outlaws rental bidding

Still, property owners felt the record-high inflation rates had forced their hand. Rents were only hiked up to keep up with rising costs of living and other maintenance costs. The Property Owners Association of New South Wales named rising interest, strata fees, and council fees among some of the many cost pressures informing rent hikes. Vice president Debra Beck-Mewing added that rents were rebounding after many property owners had dropped them during the pandemic, and would continue to increase in 2023 due to increased rental demand.

Many made homeless by the increasing rents and lack of housing supply have ended up living in cars or campervans.

“They are the hidden homeless,” said film maker Sue Thomson and producer Adam Farrington-Williams in their feature documentary ‘Under Cover’, which recorded the lives of aging women experiencing homelessness in Australia.

“Gender inequality and wage disparity are all issues that led to [their experience of homelessness] and need to be considered when looking at [the issue],” Thomson said.

Additionally, major east-coast floodings earlier this year forced about 40,000 people to evacuate their homes, Reuters reported.

Read more: CBA helps brokers hit by east coast floods

While low-cost housing is the obvious solution, there is simply not enough to go around. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare counted 440,200 social housing dwellings nationwide as of June 2021 – or an increase of less than 1% in 12 months. Social housing applicants sometimes wait up to 10 years before they are placed.

While a national housing accord is already in the works and the government has tapped the country's $3.3 trillion pension fund industry to help build affordable homes, some fear this may not be enough.

Read more: Chalmers aims to ease investor concerns about housing accord

Trina Jones, from Homelessness NSW, told Reuters that housing needed to move away from a profit-oriented goal before it could become a viable solution to the tsunami of homelessness currently looming over the country.

“It starts with a home,” Jones said. “[We] must invest in that safety net and provide support for the people to ensure their homelessness is brief and non-recurring.”

What are your thoughts on Australia’s current housing crisis? Share them in the comments below.