Clawbacks provoke intense debate but little firm data or genuine change. The industry needs to step up before regulators step in.

Are we really still talking about clawbacks? It’s been over four years since exit fees were abolished and clawbacks came into force, but in 2015 the debate was as heated as ever.

For the FBAA, reports on bank profits in early November were the straw that broke the camel’s back; CEO Peter White argued that “brokers now write more than half the new loans in the marketplace and are a pivotal part of a bank’s business and it is time they are correctly rewarded for their efforts and not punished”.

In response, the MFAA took a more conciliatory view: “Clawback is directly linked to how lenders price their product within our channel, and the MFAA accepts that it is not reasonable to expect clawback provisions to be removed altogether”. And, as usual, brokers themselves were divided, with comments on Australian Broker’s forums labelling clawbacks as anything from daylight robbery of hard-earned cash to fair punishment for dishonest churning.

All of this makes the industry sound like a broken record playing the same story of broker discontent and lender silence.

MPA set out to explore why this time it really was different, talking to the FBAA, the MFAA, lenders that have clawback fees, and one that doesn’t. What quickly became clear was that clawbacks might not have changed but the surrounding industry and regulatory landscape is rapidly being transformed.

What makes 2016 different

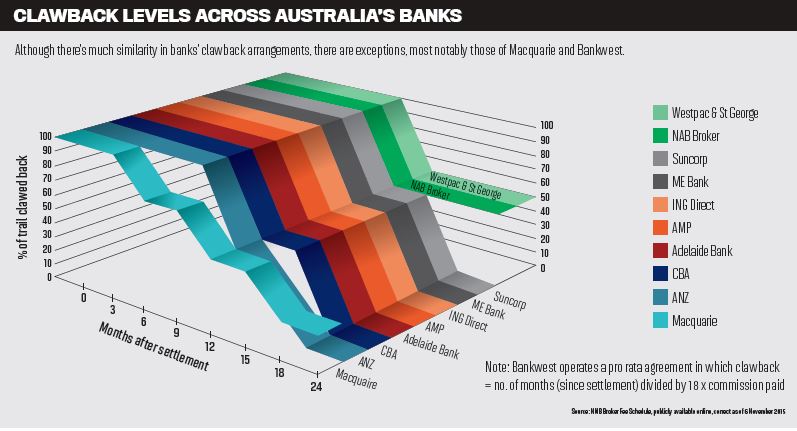

When trying to understand clawbacks, bank profits are a distraction. Clawbacks do matter, Suncorp’s head of intermediaries, Steven Degetto, told Australian brokers; they matter to commissions. “Without reasonable clawback provisions, there could be challenges to maintaining upfront commissions as they are,” he said. However, when it comes to full bank profits, clawbacks aren’t a blip on the radar; profits reflected a combination of RBA rate cuts and out-of-cycle rate rises, according to the Australian Financial Review.

As the FBAA’s Peter White told MPA, “there’s a time to and time not to [talk about clawback]. Historically, we haven’t gone further than saying ‘this isn’t right’.” What’s prompted the FBAA may have less to do with profits and much more to do with having the legal grounds (or at least believing they do) in order to move against clawback.

“We’ve got more evidence than what we need right now to continue with this,” White claimed. “We have our solicitors looking at this and have had for some weeks, prior to us talking about it … there’s a whole host of changes in law that bring this even more into focus.”

Indeed, days after MPA spoke to White, he met Assistant Treasurer Kelly O’Dwyer and afterwards stated that “the minister’s office is going to review my historic submissions and data on this issue, and we are hopeful of a positive outcome soon on this potentially nasty issue”.

Tellingly, White also connected the meeting with ASIC’s forthcoming review of brokers’ remuneration, confident that further discussions “will help all parties find the best outcomes”.

ASIC’s remuneration review may well be the game changer for the clawback debate. When MPA originally asked White whether clawbacks could become part of the review – given they factor into commission, as Degetto argued – White noted that “it is an issue they need to be thinking about”. Similarly, MFAA CEO Siobhan Hayden’s view was that “I suppose if you do look at the remuneration model it does form part of it, so it would be reasonable for it to be reviewed as part of it”.

At the time of writing, ASIC’s remuneration review had not begun (it’s scheduled for late 2016), nor had specific areas of inquiry been outlined. Whether clawbacks could count as ‘conflicted remuneration’, which is the Treasury’s stated target, is open to question, as clawbacks are designed to prevent clients from changing lenders, even when a better product could become available due to rate rises. Either way, the industry will have to prepare for a worst-case scenario, in which regulators take it upon themselves to determine clawbacks.

How the industry could deal with clawbacks

One attempt to collaboratively address the issue of clawbacks is the MFAA’s ‘broker best practice’ procedures for lenders. ANZ and NAB Broker were named as lenders that redirected broker clients back to their brokers if they made enquiries direct to the bank, to avoid brokers suffering clawback for internal bank refinancing. Additionally, aggregators including Connective, FAST and AFG confirmed they would intervene and support brokers in harsh cases of clawback, such as 23 months into a 24-month clawback period.

NAB Broker recently released a report, Engaging Consumers and Empowering Brokers, which highlighted the damage brokers could be doing to customer relations by not providing a post-settlement service.

General manager Steve Kane claimed that “we’ve saved a significant amount of trail for a significant number of brokers, simply because we’ve acted, keeping the broker primacy front of mind. Providing the customer doesn’t say, ‘I don’t want anything to do with that person ever again’, then we don’t do that”.

General manager Steve Kane claimed that “we’ve saved a significant amount of trail for a significant number of brokers, simply because we’ve acted, keeping the broker primacy front of mind. Providing the customer doesn’t say, ‘I don’t want anything to do with that person ever again’, then we don’t do that”.

As Kane indicated, the broker best practice approach does require brokers to prove they’ve provided a high level of post-settlement service. And as the MFAA’s Hayden insisted, “maybe fi ve years ago you could have waited 12 hours to get back to a customer, in relation to a query; you just can’t do that any more. You’ve got to get back to them fairly quickly, and for those brokers who aren’t doing that, that’s where they’re losing the deals”.

There are other issues with the MFAA’s approach. For a start, not everybody is convinced of its necessity. ME Bank’s Lino Pellacia told MPA that “we do not need to manage contentious clawback cases as our offerings are always transparent – our advertised rate is the same in all channels, and we stand by our principal of not undercutting”.

Moreover, there’s no actual broker best practice charter or written agreement. Hayden explained that “we don’t have people signing on the dotted line if they’re going to do it; it’s more about tacit approval and engagement and cooperation”. Broker best practice sits uneasily with the FBAA’s goal, which is the end to clawbacks if the circumstances are beyond the broker’s control. A customer could decide to refinance with another lender even if the broker was keeping in regular contact and urging them not to. However, the FBAA’s campaign has no involvement from lenders – so presumably would have to be forced upon them – whereas Hayden argues that the MFAA’s lender forum and aggregator forums are bringing together major players.

“When it comes to clawbacks I’ve engaged lenders and said, ‘wouldn’t it be great if we all took a leadership role and worked together in a partnership model?’ ” she says.

It’s possible that lenders could take their own action on clawbacks, independent of brokers and industry bodies. La Trobe Financial is a rare example of a lender that has never introduced clawbacks. Vice president Cory Bannister blames clawbacks on “supercharged upfront commissions … which are only profi table for that lender if that loan remains in place for at least two or more years”.

La Trobe says they pay a “reasonable upfront fee … reflecting the true economic value of the loan based on expected loan revenue and term, to compensate the broker for work done”.

Correspondingly, La Trobe’s upfront commission is slightly lower than other lenders’, at 0.50% (at the time of writing). They claim churn isn’t a problem due to competitive products and brokers now being highly unwilling to damage the client experience, and certainly La Trobe’s arguments will resonate with brokers. However, it’s highly debatable whether brokers would accept an across-the-board reduction on upfront commission in return for an end to clawbacks.

Finally, despite the ban on exit fees, brokers are still legally allowed to pass clawbacks on to consumers, if they write it into their client agreements. This has proved to be disastrous: Home Loan Experts found themselves in a media row back in September 2014 when they tried to claim back from a young family, and although Home Loan Experts still have the rule on their books, major franchises Aussie, Mortgage Choice and Yellow Brick Road have publicly disavowed this policy.

Need for clarity

Rather than wait for regulators, the industry has the means and institutions to create its own rules for clawbacks. What’s desperately lacking is concrete data to give decision-makers the confidence to take action.

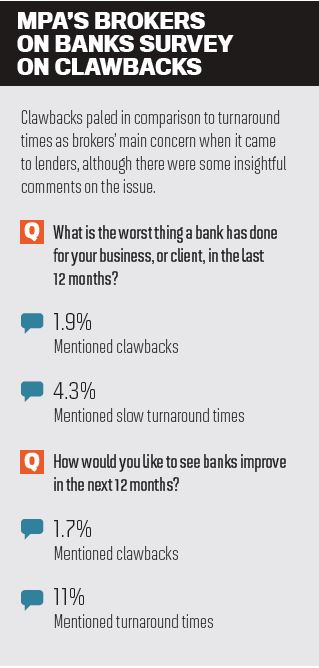

The MFAA originally claimed that 1–2% of total loans transacted within a year were normally exposed to a clawback. When MPA asked Hayden where this figure came from, she replied that “that’s from the last 12 months going around the country and talking about clawback at every single ‘Paving the Road’ session; it’s universally accepted it’s only 2% of your loans in a year”.

It isn’t just the MFAA that is guilty of presenting anecdotal evidence as fact. The FBAA’s White played down the need for a proper study of clawback, claiming they already had enough evidence to support their case. “I got bombarded with emails from people who support what we do,” White said. “I talked about this at our conference and the whole room stood up in applause.”

NAB Broker’s above-mentioned report, which talked to consumers, gave brokers some idea of what’s expected of after-settlement service, as did MPA’s own Consumers on Brokers report. NAB Broker’s report showed that 29% of broker applicants wanted to hear about new products related to their service and 28% wanted to hear about refinancing, while MPA’s report found that 77% of consumers who had used a broker wanted at least an annual check-up, if not more frequently, and 52% wanted to hear about refinancing.

The MFAA’s Hayden advises brokers to schedule, standardise and then document their engagement with clients, to provide protection in the event of clawback.

Reports are admirable, but lenders need to be willing to share their data on clawbacks – how many, how much and how long after loan settlement they take place. It may be, as Hayden puts it, that clawbacks are “a minor environmental issue” affecting an incompetent minority of brokers. Or they could be tweaked to protect responsible brokers: White concedes that “it may even be that a loan needs to go longer than three months or six months, although I don’t think that’s necessary”.

Clawbacks aren’t a direct threat to the industry’s reputation, but they are a crucial test of whether the industry has the ability to regulate itself. If regulators find they need to step in, or clawback disputes end up in court, it could set a precedent for regulator intervention in other potentially more important areas of the third-party channel. To avoid this, the industry needs to recognise that vast gulf between spirited debate and real action.

For the FBAA, reports on bank profits in early November were the straw that broke the camel’s back; CEO Peter White argued that “brokers now write more than half the new loans in the marketplace and are a pivotal part of a bank’s business and it is time they are correctly rewarded for their efforts and not punished”.

In response, the MFAA took a more conciliatory view: “Clawback is directly linked to how lenders price their product within our channel, and the MFAA accepts that it is not reasonable to expect clawback provisions to be removed altogether”. And, as usual, brokers themselves were divided, with comments on Australian Broker’s forums labelling clawbacks as anything from daylight robbery of hard-earned cash to fair punishment for dishonest churning.

All of this makes the industry sound like a broken record playing the same story of broker discontent and lender silence.

MPA set out to explore why this time it really was different, talking to the FBAA, the MFAA, lenders that have clawback fees, and one that doesn’t. What quickly became clear was that clawbacks might not have changed but the surrounding industry and regulatory landscape is rapidly being transformed.

What makes 2016 different

When trying to understand clawbacks, bank profits are a distraction. Clawbacks do matter, Suncorp’s head of intermediaries, Steven Degetto, told Australian brokers; they matter to commissions. “Without reasonable clawback provisions, there could be challenges to maintaining upfront commissions as they are,” he said. However, when it comes to full bank profits, clawbacks aren’t a blip on the radar; profits reflected a combination of RBA rate cuts and out-of-cycle rate rises, according to the Australian Financial Review.

As the FBAA’s Peter White told MPA, “there’s a time to and time not to [talk about clawback]. Historically, we haven’t gone further than saying ‘this isn’t right’.” What’s prompted the FBAA may have less to do with profits and much more to do with having the legal grounds (or at least believing they do) in order to move against clawback.

“We’ve got more evidence than what we need right now to continue with this,” White claimed. “We have our solicitors looking at this and have had for some weeks, prior to us talking about it … there’s a whole host of changes in law that bring this even more into focus.”

Indeed, days after MPA spoke to White, he met Assistant Treasurer Kelly O’Dwyer and afterwards stated that “the minister’s office is going to review my historic submissions and data on this issue, and we are hopeful of a positive outcome soon on this potentially nasty issue”.

Tellingly, White also connected the meeting with ASIC’s forthcoming review of brokers’ remuneration, confident that further discussions “will help all parties find the best outcomes”.

ASIC’s remuneration review may well be the game changer for the clawback debate. When MPA originally asked White whether clawbacks could become part of the review – given they factor into commission, as Degetto argued – White noted that “it is an issue they need to be thinking about”. Similarly, MFAA CEO Siobhan Hayden’s view was that “I suppose if you do look at the remuneration model it does form part of it, so it would be reasonable for it to be reviewed as part of it”.

At the time of writing, ASIC’s remuneration review had not begun (it’s scheduled for late 2016), nor had specific areas of inquiry been outlined. Whether clawbacks could count as ‘conflicted remuneration’, which is the Treasury’s stated target, is open to question, as clawbacks are designed to prevent clients from changing lenders, even when a better product could become available due to rate rises. Either way, the industry will have to prepare for a worst-case scenario, in which regulators take it upon themselves to determine clawbacks.

How the industry could deal with clawbacks

One attempt to collaboratively address the issue of clawbacks is the MFAA’s ‘broker best practice’ procedures for lenders. ANZ and NAB Broker were named as lenders that redirected broker clients back to their brokers if they made enquiries direct to the bank, to avoid brokers suffering clawback for internal bank refinancing. Additionally, aggregators including Connective, FAST and AFG confirmed they would intervene and support brokers in harsh cases of clawback, such as 23 months into a 24-month clawback period.

NAB Broker recently released a report, Engaging Consumers and Empowering Brokers, which highlighted the damage brokers could be doing to customer relations by not providing a post-settlement service.

General manager Steve Kane claimed that “we’ve saved a significant amount of trail for a significant number of brokers, simply because we’ve acted, keeping the broker primacy front of mind. Providing the customer doesn’t say, ‘I don’t want anything to do with that person ever again’, then we don’t do that”.

General manager Steve Kane claimed that “we’ve saved a significant amount of trail for a significant number of brokers, simply because we’ve acted, keeping the broker primacy front of mind. Providing the customer doesn’t say, ‘I don’t want anything to do with that person ever again’, then we don’t do that”.As Kane indicated, the broker best practice approach does require brokers to prove they’ve provided a high level of post-settlement service. And as the MFAA’s Hayden insisted, “maybe fi ve years ago you could have waited 12 hours to get back to a customer, in relation to a query; you just can’t do that any more. You’ve got to get back to them fairly quickly, and for those brokers who aren’t doing that, that’s where they’re losing the deals”.

There are other issues with the MFAA’s approach. For a start, not everybody is convinced of its necessity. ME Bank’s Lino Pellacia told MPA that “we do not need to manage contentious clawback cases as our offerings are always transparent – our advertised rate is the same in all channels, and we stand by our principal of not undercutting”.

Moreover, there’s no actual broker best practice charter or written agreement. Hayden explained that “we don’t have people signing on the dotted line if they’re going to do it; it’s more about tacit approval and engagement and cooperation”. Broker best practice sits uneasily with the FBAA’s goal, which is the end to clawbacks if the circumstances are beyond the broker’s control. A customer could decide to refinance with another lender even if the broker was keeping in regular contact and urging them not to. However, the FBAA’s campaign has no involvement from lenders – so presumably would have to be forced upon them – whereas Hayden argues that the MFAA’s lender forum and aggregator forums are bringing together major players.

“When it comes to clawbacks I’ve engaged lenders and said, ‘wouldn’t it be great if we all took a leadership role and worked together in a partnership model?’ ” she says.

It’s possible that lenders could take their own action on clawbacks, independent of brokers and industry bodies. La Trobe Financial is a rare example of a lender that has never introduced clawbacks. Vice president Cory Bannister blames clawbacks on “supercharged upfront commissions … which are only profi table for that lender if that loan remains in place for at least two or more years”.

La Trobe says they pay a “reasonable upfront fee … reflecting the true economic value of the loan based on expected loan revenue and term, to compensate the broker for work done”.

Correspondingly, La Trobe’s upfront commission is slightly lower than other lenders’, at 0.50% (at the time of writing). They claim churn isn’t a problem due to competitive products and brokers now being highly unwilling to damage the client experience, and certainly La Trobe’s arguments will resonate with brokers. However, it’s highly debatable whether brokers would accept an across-the-board reduction on upfront commission in return for an end to clawbacks.

Finally, despite the ban on exit fees, brokers are still legally allowed to pass clawbacks on to consumers, if they write it into their client agreements. This has proved to be disastrous: Home Loan Experts found themselves in a media row back in September 2014 when they tried to claim back from a young family, and although Home Loan Experts still have the rule on their books, major franchises Aussie, Mortgage Choice and Yellow Brick Road have publicly disavowed this policy.

Need for clarity

Rather than wait for regulators, the industry has the means and institutions to create its own rules for clawbacks. What’s desperately lacking is concrete data to give decision-makers the confidence to take action.

The MFAA originally claimed that 1–2% of total loans transacted within a year were normally exposed to a clawback. When MPA asked Hayden where this figure came from, she replied that “that’s from the last 12 months going around the country and talking about clawback at every single ‘Paving the Road’ session; it’s universally accepted it’s only 2% of your loans in a year”.

It isn’t just the MFAA that is guilty of presenting anecdotal evidence as fact. The FBAA’s White played down the need for a proper study of clawback, claiming they already had enough evidence to support their case. “I got bombarded with emails from people who support what we do,” White said. “I talked about this at our conference and the whole room stood up in applause.”

NAB Broker’s above-mentioned report, which talked to consumers, gave brokers some idea of what’s expected of after-settlement service, as did MPA’s own Consumers on Brokers report. NAB Broker’s report showed that 29% of broker applicants wanted to hear about new products related to their service and 28% wanted to hear about refinancing, while MPA’s report found that 77% of consumers who had used a broker wanted at least an annual check-up, if not more frequently, and 52% wanted to hear about refinancing.

The MFAA’s Hayden advises brokers to schedule, standardise and then document their engagement with clients, to provide protection in the event of clawback.

Reports are admirable, but lenders need to be willing to share their data on clawbacks – how many, how much and how long after loan settlement they take place. It may be, as Hayden puts it, that clawbacks are “a minor environmental issue” affecting an incompetent minority of brokers. Or they could be tweaked to protect responsible brokers: White concedes that “it may even be that a loan needs to go longer than three months or six months, although I don’t think that’s necessary”.

Clawbacks aren’t a direct threat to the industry’s reputation, but they are a crucial test of whether the industry has the ability to regulate itself. If regulators find they need to step in, or clawback disputes end up in court, it could set a precedent for regulator intervention in other potentially more important areas of the third-party channel. To avoid this, the industry needs to recognise that vast gulf between spirited debate and real action.