(TheNicheReport.com) -- If you're old enough to remember the 1980s, you've undoubtedly heard the conventional wisdom about retirement investing from a slew of financial advisors. Here's how it goes: Invest in equities, through quality mutual funds, diversify properly relative to your tolerance for risk, hang in there for the long-term… don’t panic and everything will work out fine… you'll achieve your financial goals and enjoy a comfortable retirement. Or something very close to that, right? Basically, ever since Oliver Stone's movie Wall Street, we've all been told that the stock market will go up and it'll go down, but over the "long-term" we’re all but certain to do better investing there than anywhere else.

Today, something like 75 percent of all Americans are invested in the stock market in one way or another, and they do so believing that this is the path to accumulating the amounts they need to retire comfortably. Americans invest in the stock market through their employer-sponsored retirement plans, their IRAs, their pensions, insurance policies, and more. It's become accepted conventional wisdom: If you want to invest for the future, you need to have most of your savings in stocks. It seems like a maxim that’s been around since Aesop’s Fables, but that’s simply not the case. Consider that in August of 1982, the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit 772, but by that year's end, an interest rate fed Bull Market was born and it would last for an astounding and unprecedented quarter of a century. On October 9, 2007, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at a record 14,164.53. Seven hundred and seventy two to fourteen thousand and change? Now, that’s what I call a bull market.

So, what is the definition of a bull market? That one is easy. Mandelman’s Dictionary defines “bull market” as: A temporary condition that makes investors feel like geniuses. Well, the proverbial jury has now been in for some time and I'm sorry to say that the news is not good: We've been lied to. Deceived. Misled. Manipulated. And, as a result, our ability to save the amounts we need to retire comfortably is… well, shall we say… somewhere between lacking and nonexistent. We've been confounded by charts. Stunned by statistics. And buffaloed by B.S. Avoiding Future Financial Shock If you're under forty years old, chances are there's no talking to you about investing for your future. If you're over forty, you're looking at 65 as being just around the corner, and it's now critically important that you take a moment to take stock. No, not buy stock JP, I said take stock.

As baby boomers, our retirement years are approaching faster than any of us wants to think about. If you don't start to scrutinize your views on, and skills related to investing for your future years, then what's in store is likely to come as quite a shock. To avoid that future shock, we need to better understand how we all got here, so we can change the way things go, going forward. Understanding Bubbles… We seem to have a love-hate relationship with bubbles. It all started in mid-1980s, when "greed was good," corporate raiders were modern day cowboys, and junk bonds meant that money was flowing through Wall Street like lava from Mt. Vesuvius. Of course, much like what happened when Vesuvius erupted above the town of Pompeii in 70 AD, it all soon came to a standstill. The "Black Monday" market crash of October 1987 signaled the end of an era. Drexel Burnham Lambert, Mike Milliken, Charlie Keating, Ivan Boseky, and the other names that had by then permeated our lexicon as being leaders of American business, all ended up to be major disappointments, to say the least. The bubble popped, S&Ls went under, and suffice it to say… it was a real mess that was certain to trigger a bad recession.

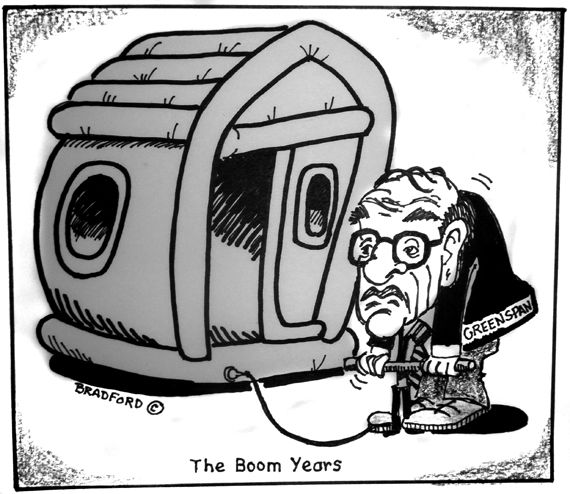

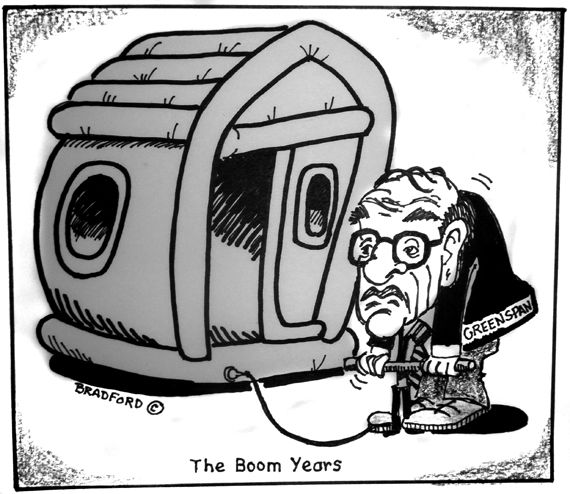

All of a sudden we went from thinking that having a new BMW was cool, to viewing a mini-van and a savings account as much cooler. Then, after weathering the recessionary storm of the early 1990s, we saw little company named Netscape go public, and soon three initials were on everyone's mind: I, P and O. Everyone was "doing it". We heard stories of business plans written on napkins by college drop-outs raising innumerable millions, our neighbors all seemed to have bought Cisco Systems at $6 a share, and tiny AOL, who was attempting to wallpaper the planet with free CD ROMs would soon be buying out media mega-giant Time Warner. It didn't make a lick of sense to many people, me included, but the stock market was flying high, a "new economy" had supposedly arrived, and early retirement became the buzzword of the day. Cab drivers were day trading, and just about everyone over the age of 18 had a stockbroker on speed dial. Never mind that Alan Greenspan was warning of irrational exuberance and Warren Buffet was sitting on the sidelines. Never mind that the companies we were investing in didn't make any money.

Other people at least appeared to be getting rich, so in the spirit of Sutter’s Mill, we jumped in with both feet. Then, on April 10th, 2000, the bubble popped… again. American consumers lost $7.3 trillion as a result, and prayers rang out across the land. We promised God that we would only buy bonds for the rest of our lives, if Cisco would just come back to $84 a share, even for a moment. IPO, as it turned out, didn’t just stand for Initial Public Offering. It also stood for: It's Probably Overpriced. When the dot-com bubble popped in 2000, the United States was plunged into a recession that many feared could become quite serious, as the prospect of "deflation" came into view. But, the Federal Reserve under Greenspan, determined to avoid a replay of the 1970's economic malaise, lowered rates and opened the floodgates of capital.

Almost overnight, real estate became our savior-du-jour, and soon it would be our homes that would save us from ourselves. Someone that lost his or her bet that Amazon.com would reach $400 a share, could still be assured a comfortable retirement simply by owning a home and perhaps investing in a duplex. Or, as my good friend Ernie Banks of the Chicago Cubs might have said back then: It’s a beautiful day for an open house… Let’s buy two. (Sorry Ernie, I couldn’t help that.) "Real estate is by far the safest investment you can make. Housing prices will never fall like share prices." That was the thinking way back then, remember? "Pets.com may go to zero, but a house simply can't do that."

People ignored anyone suggesting that yet another bubble was in the making. And when I say “people,” I’m including the Chairs of the Federal Reserve Bank, among countless others. The fact that housing prices had fallen after previous booms, such as in 1990, didn't seem to matter. "This time is different", was the thinking of the day. Of course, that was exactly what the stock market analysts had said in the latter half of 1990s, but we didn't seem to remember that far back for some inexplicable reason.

Here's what the venerable Economist magazine printed in May of 2002: IF THERE is one single factor that has saved the world economy from a deep recession it is the housing market. Despite the sharp fall in share prices and a worldwide plunge in industrial production, business investment and profits, consumer spending has held up relatively well in America, supported by low interest rates and the wealth-boosting effects of rising house prices. Over the 12 months to February average house prices in America rose by 9%, the biggest real increase on record in America. Yes, we were all blowing hot air into yet another bubble and by 2005 that bubble was approaching the size of Saturn.

Here's what the Economist wrote in June of 2005: PERHAPS the best evidence that America's house prices have reached dangerous levels is the fact that house-buying mania has been plastered on the front of virtually every American newspaper and magazine over the past month. Such bubble-talk hardly comes as a surprise to our readers. We have been warning for some time that the price of housing was rising at an alarming rate all around the globe, including in America. Now that others have noticed as well, the day of reckoning is closer at hand. It is not going to be pretty. How the current housing boom ends could decide the course of the entire world economy over the next few years. Never before in history of the world had housing values gone up so fast, so much, and for such a long period of time. The rising property prices that had helped prop up our economy after the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, but it was about to get ugly.

According to estimates published by the Economist in the second half of 2005: The total value of residential property in developed economies rose by more than $30 trillion over the past five years, to over $70 trillion, which is an increase equivalent to 100% of those countries' combined GDPs. Not only does this dwarf any previous house-price boom, it is larger than the global stock market bubble in the late 1990s (an increase over five years of 80% of GDP) or America's stock market bubble in the late 1920s (55% of GDP). In other words, it looks like the biggest bubble in history.

Of course, by the time 2007 appeared on our calendars, the real estate bubble had popped over a year before and many of us, for THE THIRD TIME, were again trying to get the gum out of our collective hair. The economic crisis we now face, as a result of the giant real estate bubble having popped, has decimated our wealth, and has only just begun to destroy our national psyche. So, three bubbles… we're three for three. What's next? Are we waiting for yet another GET RICH NOW, ASK ME HOW OPPORTUNITY, through which we can finally catch up so we can retire in style? Or will we finally learn that we can't afford any more of those fabulous, sure thing opportunities? It is the view of many self-proclaimed "experts" that it is we investors that are the culprits. We, as the thinking goes, are our own worst enemy. It is simply human greed that creates the bubbles that cause us such financial harm. And therefore, since greed is here to stay, we are doomed to repeat our past behaviors. But is this easily reached assumption really true? Are we really just greedy opportunists receiving our just desserts as the bubbles we create inevitably pop?

The answer is unequivocally "let's hope not". There's no question that greed is an inherently human trait that we are all capable of exhibiting under the right circumstances. But, to assume that greed is what fuels our collective investor psyche in my mind is simply too cynical, along with feeling like a conclusion far too easily reached. Consider, for example, that most of the people that saw their 401(k) balances decimated as a result of the dot-com bubble's demise weren't being greedy when they jumped on the technology bandwagon. Greedy people, one would think, would be more careful… more crafty. Greedy people don't leave 75% of their retirement investments in their own company’s stock, and then sink the rest into a technology growth fund. I would tell you that it’s not greed that drives us to our lemming like self-destructive behavior.

People jump on such bandwagons, not because they’re greedy, but because they don't want to be left out of what everyone else is doing, and from which many appear to be benefiting. Being left out sucks… big time. We hated being left out in elementary school and high school, and we don't like it any more as adults. No one wants to be the one still looking for an empty chair when the music stops. The feeling of being left out, like greed, is a basic human trait, but it's much more commonly shared than greed. There are unquestionably some among us that are greedy, but none of us relishes the idea of being left out. So, while we do provide the air that inflates our market's bubbles, it's not being driven by all-too-human greed. We are simply trying to ensure that we are not left out of a party to which so many of our peers appear to have been invited. Human traits, such as greed are not things we can change… such traits can only be controlled to varying degree. However, human beings will never like the feeling of being left out… not even for a moment. With all of this in mind, it shouldn't be difficult to imagine how investment bubbles keep happening around the kitchen tables across this country.

"Honey, we should buy more technology stocks… Joe and Mary bought more technology stocks… why can't we buy more technology stocks? Or, more recently: "Honey, we should buy another house… Joe and Mary just bought another house… Tom just bought a place in the desert… everyone but us has at least two houses… shouldn't we buy another house? We don't want to be left out!!" Left Out of a Financially Secure Future During the technology bubble of the last half of the 1990s many of us were contemplating an early retirement as a result of what looked like was newfound investor prowess. Today, we're not entirely sure that we will be able to retire at all, and few of us can remember the name of the last stockbroker we used. Just try mentioning that you received a "tip" from a broker at an upcoming social gathering and you'll quickly see how risk averse we've actually become. Oh sure, we haven't appeared to be all that gun shy these last few years, but that's only because we were floating around in the real estate bubble.

But make no mistake about it… those that jumped into real estate were driven by a need for the assumed relative safety of the real estate market. No one thought investing in real estate could be overly risky because everyone was doing it, and because houses, regardless of their purchase price, could not end up being worth nothing, as was the case for shares of Pets.com and Home Grocer. Those that got into real estate later in the game, however, did so not out of greed… but to ensure that they would not be left out. Numerous studies conducted after the dot-com collapse support this hypothesis. For example, many people reported feeling much less embarrassed about losing money on a popular stock that half the world owns - like AOL or Yahoo - than about losing on an unknown or unpopular stock. As long as everyone's losing… or winning… we're okay with it. This is another example of why we're terrible at investing: We buy what's "hot". All data shows that money flows into high profile mutual funds much faster than the money that flows out of underperforming ones. As a result we continually buy high, and sell low… and it would seem are destined to do so. There are many other aspects of human behavior that impact our ability to invest effectively. Some studies show that we're more scared of losses, than we are happy about gains.

Anchoring is the concept that shows that people tend to place too much credence in recent market events and opinions, and ignore historical, long-term averages and probabilities. And most of us are just generally overconfident. Countless studies show that people generally rate themselves as being above average in their abilities. We often overestimate the precision of our knowledge, and our knowledge relative to others. We're human, and therefore… we're doomed? It would be easy to reach the conclusion that as flawed human beings we are doomed to repeat our failures as far as investing or preparing for our future goes, but I don't believe that has to be true. I believe that, by understanding our inadequacies, we can overcome our established tendencies.

The Solution: Change your view of what you don't want to be left out of… It's time to take hold of the law of nature that dictates that we, as human beings, don't want to feel left out, and harness its power to our advantage. We can learn from the past… if we want to. Consider this: What's the one thing, more than anything else, that you don't want to be left out of: A comfortable retirement, right? Imagine being left out of that. Imagine watching your friends and relatives vacationing together, while you remain at home constrained by a budget far less than you lived with throughout your working life. Perfect. Now that you have the time to travel, you can't afford to. Imagine what it would be like to run out of money long before reaching your life expectancy… your last ten years of life spent struggling to exist below the poverty line. Are you imagining the horror of that situation? Good. Now, compare that with feeling of being left out of buying Cisco Systems at $6 a share, or not buying real estate when everyone else was. If the latter is a pinprick, the former is amputation of both your arms and legs… right? Once you realize that the most important thing not to be left out of is your own comfortable retirement, you can begin to change your perspective on what you need to do differently in order to make sure that you're not.

Savings and Returns on Investments The first step is to save as much as you can, but for the purposes of this article, that's a given. The next step, as any investment advisor will tell you, is to invest those savings, within a certain tolerance for risk, in order to maximize your returns on investment or ROI. That's what we're told, isn't it? If we are to reach our financial goals, it's the long-term performance of our investments that reigns supreme? And it makes sense, on the surface anyway. Of course you should take steps to maximize your ROI, right? If you see one fund doing better than another, it stands to reason that you should put your money where the returns are higher, assuming the risk of doing so is not significantly greater. Doesn't it? I'm not at all sure it does, how about that? In fact, I'm pretty darn sure it's all a pile of crap. ROI is investment advisor horsepucky, nothing more. It’s twaddle, of the highest order. I'm going to tell you something you may not have considered before: Chasing ROI is a fool's errand… a waste of time… essentially, it’s entirely pointless. Why? Why would it not matter what your ROI, or return on investment was?

How can that be? Is that what you're thinking? Because that is what you should be thinking… that's certainly what I would have been thinking before I spent almost all of 2008 intensively studying the markets as related to retirement investing. Now, I'm thinking very differently. ROI doesn't matter for several reasons. The most important one is that your up years don’t really matter nearly as much as you probably think they do. In reality, it's the down years that kill you. If you had invested over the last 25 years in order to earn just a 3-4% annual return every year and never a penny more, but you could skip all of the down years… chances are you'd be a lot better off today. The other reason that attempting to maximize ROI isn't so important is that we are terrible at it. According to John Bogle at Vanguard, between 1980 and 2005, the average annual return was 12.3%, but the average investor earned just 7.3%.

Here we go again… we love to buy high and sell during the fall of ‘08. Consider what Warren Buffet had to say about the last century and the century ahead in his letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders: "Over the last century the Dow went from 66 to 11,497. While this may seem like enormous growth on the surface, compounded annually, it's just 5.3% per year. In this century, if investors matched that return, the Dow would close at 2,000,000 by year end 2099." Two million? The Dow Jones Industrial Average at 2,000,000? I know that's ninety years from now, but still. No one thinks the DOW will ever see two million. The Oracle of Omaha went on to say this: "And anyone who expects to earn 10% annually from equities during this century is implicitly forecasting the Dow to reach 24,000,000 by the year 2100. If your advisor talks to you about such double digit returns from equities going forward, explain this math to him… not that it will faze him. Many helpers are apparently direct descendants of the queen in Alice in Wonderland who said: Why, sometimes I've believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast." Here are the facts about the markets:

And it’s likely that you’ll never recover… your nest egg will run out before you do just because of one year’s negative returns in the all-powerful stock market. You need to focus on the cash flow your accumulated savings will provide during your retirement years. And not just "maybe” cash flow, but "for sure" cash flow. The kind that used to be called a pension until the Wall Street cabal convinced us, and our government, that the portability of self-directed defined contribution plans was preferable to the stodgy and oh-so-dull defined benefit plans. I saw the movie "Jaws" when I was 12, and as a result was too scared to swim in the ocean until I was 30. I saw the movie "Wall St." when I was almost 30, and as a result I've been losing so much money to land sharks ever since that now I can't even afford to vacation in a locale where I might be eaten by a real shark. It's been a rocky ride, these past 25 years, to say the very least. We've had some good years and some utterly ruinous ones.

And only the eternally disingenuous, self-delusional, and ethically bankrupt pricks who brought us the economic collapse in which we now find ourselves could possibly still have the chutzpah to be perpetuating the idea that the stock market is where we should all be investing our retirement savings. It's beyond being merely bad advice… it’s absolute claptrap. The stock market is equivalent to gambling, pure and simple… except you don't get the free drinks like you do when gambling in Las Vegas. We all need to come to terms with the fact that WE… and by “we” I do mean you… are at best nothing special when it come to investing, and that even though we may have a financial advisor whose personality we may think we like… it's OUR money and OUR job to make sure we don’t lose so much that we don’t reach OUR goals. You might remember the definition of a bull market: A temporary condition that makes investors feel like geniuses. We need to stop listening to smart-sounding drivel from people in snappy suits about the market’s historical average returns, because historically, nobody has ever earned them.

And we better start paying attention to the ubiquitous phrase that follows those historical perspective presentations without fail: "Past performance is no assurance of future results.” I think we should add a few phrases to such disclaimers, like how about: “Returns shown in slide shows are smaller than they appear.” In the U.S. alone there are more than 3.5 trillion books on "how to become a better investor" published each year. That's more than the number published on the subjects of "diet and exercise," and roughly the same number written about Real Estate investing in 2007 that claimed it as eminently safe. Haven't we learned enough by now? Are we simply doomed to continually give back all of our gains and then some every few years until our portfolios would have performed better had they been left inside a SimmonsBeautyrest®? Are we that pie-eyed? Greedy? Short-term memory loss? A learning disability? Restless leg syndrome… what's the deal? We have to have learned better by now, right?

Oh sure… our "light bulb" is on alright… but even with market meltdowns, irrational rallies, Jim Kramer, and unemployment continuing to go in the wrong direction… and now Americans with dollars soon to be used in some countries as memo pads, too many of us are still sitting at home using that light bulb’s glow to read the list of "Hot Stocks for 2010," in Rich & Richer Magazine. Again? Seriously? Look, I'm no financial genius, and at 48 years old I’m not claiming to know everything about retirement. But I'm damn positive about one thing: Running out of money at 83, and living until 93, would be... let's just say "far from ideal" and leave it at that. So, why don't we do something about our situation? Change our ridiculous and irrational behavior. Dump our investment funds that, in truth, we know nothing about, and start saving for our retirement years through vehicles like annuities that offer guarantees that limit our losses in down years, and life insurance policies that can provide us with a source of funds that can be accessed tax-free. Why that's an easy question to answer: We can't... not right now, anyway.

Maybe when the markets come back… don't want to miss the "bounce" don't you know! Well, alrighty then. I guess all I can say is: Hit me. And bring me another one of those cocktails with the little umbrellas in them, would you? Viva Lasfriggen' Vegas, Daddy-O! Oh, and it’s split the sixes, right? Right. Mandelman out. Ergo bibamus.

Martin Andelman is a staff writer for The Niche Report. He also writes an almost daily column on Ml-Implode.com called Mandelman Matters. He also publishes a Monthly Museletter and you can follow "Mandelman" on Twitter. Send your reponses to [email protected].

Martin Andelman is a staff writer for The Niche Report. He also writes an almost daily column on Ml-Implode.com called Mandelman Matters. He also publishes a Monthly Museletter and you can follow "Mandelman" on Twitter. Send your reponses to [email protected].

Today, something like 75 percent of all Americans are invested in the stock market in one way or another, and they do so believing that this is the path to accumulating the amounts they need to retire comfortably. Americans invest in the stock market through their employer-sponsored retirement plans, their IRAs, their pensions, insurance policies, and more. It's become accepted conventional wisdom: If you want to invest for the future, you need to have most of your savings in stocks. It seems like a maxim that’s been around since Aesop’s Fables, but that’s simply not the case. Consider that in August of 1982, the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit 772, but by that year's end, an interest rate fed Bull Market was born and it would last for an astounding and unprecedented quarter of a century. On October 9, 2007, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at a record 14,164.53. Seven hundred and seventy two to fourteen thousand and change? Now, that’s what I call a bull market.

So, what is the definition of a bull market? That one is easy. Mandelman’s Dictionary defines “bull market” as: A temporary condition that makes investors feel like geniuses. Well, the proverbial jury has now been in for some time and I'm sorry to say that the news is not good: We've been lied to. Deceived. Misled. Manipulated. And, as a result, our ability to save the amounts we need to retire comfortably is… well, shall we say… somewhere between lacking and nonexistent. We've been confounded by charts. Stunned by statistics. And buffaloed by B.S. Avoiding Future Financial Shock If you're under forty years old, chances are there's no talking to you about investing for your future. If you're over forty, you're looking at 65 as being just around the corner, and it's now critically important that you take a moment to take stock. No, not buy stock JP, I said take stock.

As baby boomers, our retirement years are approaching faster than any of us wants to think about. If you don't start to scrutinize your views on, and skills related to investing for your future years, then what's in store is likely to come as quite a shock. To avoid that future shock, we need to better understand how we all got here, so we can change the way things go, going forward. Understanding Bubbles… We seem to have a love-hate relationship with bubbles. It all started in mid-1980s, when "greed was good," corporate raiders were modern day cowboys, and junk bonds meant that money was flowing through Wall Street like lava from Mt. Vesuvius. Of course, much like what happened when Vesuvius erupted above the town of Pompeii in 70 AD, it all soon came to a standstill. The "Black Monday" market crash of October 1987 signaled the end of an era. Drexel Burnham Lambert, Mike Milliken, Charlie Keating, Ivan Boseky, and the other names that had by then permeated our lexicon as being leaders of American business, all ended up to be major disappointments, to say the least. The bubble popped, S&Ls went under, and suffice it to say… it was a real mess that was certain to trigger a bad recession.

All of a sudden we went from thinking that having a new BMW was cool, to viewing a mini-van and a savings account as much cooler. Then, after weathering the recessionary storm of the early 1990s, we saw little company named Netscape go public, and soon three initials were on everyone's mind: I, P and O. Everyone was "doing it". We heard stories of business plans written on napkins by college drop-outs raising innumerable millions, our neighbors all seemed to have bought Cisco Systems at $6 a share, and tiny AOL, who was attempting to wallpaper the planet with free CD ROMs would soon be buying out media mega-giant Time Warner. It didn't make a lick of sense to many people, me included, but the stock market was flying high, a "new economy" had supposedly arrived, and early retirement became the buzzword of the day. Cab drivers were day trading, and just about everyone over the age of 18 had a stockbroker on speed dial. Never mind that Alan Greenspan was warning of irrational exuberance and Warren Buffet was sitting on the sidelines. Never mind that the companies we were investing in didn't make any money.

Other people at least appeared to be getting rich, so in the spirit of Sutter’s Mill, we jumped in with both feet. Then, on April 10th, 2000, the bubble popped… again. American consumers lost $7.3 trillion as a result, and prayers rang out across the land. We promised God that we would only buy bonds for the rest of our lives, if Cisco would just come back to $84 a share, even for a moment. IPO, as it turned out, didn’t just stand for Initial Public Offering. It also stood for: It's Probably Overpriced. When the dot-com bubble popped in 2000, the United States was plunged into a recession that many feared could become quite serious, as the prospect of "deflation" came into view. But, the Federal Reserve under Greenspan, determined to avoid a replay of the 1970's economic malaise, lowered rates and opened the floodgates of capital.

Almost overnight, real estate became our savior-du-jour, and soon it would be our homes that would save us from ourselves. Someone that lost his or her bet that Amazon.com would reach $400 a share, could still be assured a comfortable retirement simply by owning a home and perhaps investing in a duplex. Or, as my good friend Ernie Banks of the Chicago Cubs might have said back then: It’s a beautiful day for an open house… Let’s buy two. (Sorry Ernie, I couldn’t help that.) "Real estate is by far the safest investment you can make. Housing prices will never fall like share prices." That was the thinking way back then, remember? "Pets.com may go to zero, but a house simply can't do that."

People ignored anyone suggesting that yet another bubble was in the making. And when I say “people,” I’m including the Chairs of the Federal Reserve Bank, among countless others. The fact that housing prices had fallen after previous booms, such as in 1990, didn't seem to matter. "This time is different", was the thinking of the day. Of course, that was exactly what the stock market analysts had said in the latter half of 1990s, but we didn't seem to remember that far back for some inexplicable reason.

Here's what the venerable Economist magazine printed in May of 2002: IF THERE is one single factor that has saved the world economy from a deep recession it is the housing market. Despite the sharp fall in share prices and a worldwide plunge in industrial production, business investment and profits, consumer spending has held up relatively well in America, supported by low interest rates and the wealth-boosting effects of rising house prices. Over the 12 months to February average house prices in America rose by 9%, the biggest real increase on record in America. Yes, we were all blowing hot air into yet another bubble and by 2005 that bubble was approaching the size of Saturn.

Here's what the Economist wrote in June of 2005: PERHAPS the best evidence that America's house prices have reached dangerous levels is the fact that house-buying mania has been plastered on the front of virtually every American newspaper and magazine over the past month. Such bubble-talk hardly comes as a surprise to our readers. We have been warning for some time that the price of housing was rising at an alarming rate all around the globe, including in America. Now that others have noticed as well, the day of reckoning is closer at hand. It is not going to be pretty. How the current housing boom ends could decide the course of the entire world economy over the next few years. Never before in history of the world had housing values gone up so fast, so much, and for such a long period of time. The rising property prices that had helped prop up our economy after the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, but it was about to get ugly.

According to estimates published by the Economist in the second half of 2005: The total value of residential property in developed economies rose by more than $30 trillion over the past five years, to over $70 trillion, which is an increase equivalent to 100% of those countries' combined GDPs. Not only does this dwarf any previous house-price boom, it is larger than the global stock market bubble in the late 1990s (an increase over five years of 80% of GDP) or America's stock market bubble in the late 1920s (55% of GDP). In other words, it looks like the biggest bubble in history.

Of course, by the time 2007 appeared on our calendars, the real estate bubble had popped over a year before and many of us, for THE THIRD TIME, were again trying to get the gum out of our collective hair. The economic crisis we now face, as a result of the giant real estate bubble having popped, has decimated our wealth, and has only just begun to destroy our national psyche. So, three bubbles… we're three for three. What's next? Are we waiting for yet another GET RICH NOW, ASK ME HOW OPPORTUNITY, through which we can finally catch up so we can retire in style? Or will we finally learn that we can't afford any more of those fabulous, sure thing opportunities? It is the view of many self-proclaimed "experts" that it is we investors that are the culprits. We, as the thinking goes, are our own worst enemy. It is simply human greed that creates the bubbles that cause us such financial harm. And therefore, since greed is here to stay, we are doomed to repeat our past behaviors. But is this easily reached assumption really true? Are we really just greedy opportunists receiving our just desserts as the bubbles we create inevitably pop?

The answer is unequivocally "let's hope not". There's no question that greed is an inherently human trait that we are all capable of exhibiting under the right circumstances. But, to assume that greed is what fuels our collective investor psyche in my mind is simply too cynical, along with feeling like a conclusion far too easily reached. Consider, for example, that most of the people that saw their 401(k) balances decimated as a result of the dot-com bubble's demise weren't being greedy when they jumped on the technology bandwagon. Greedy people, one would think, would be more careful… more crafty. Greedy people don't leave 75% of their retirement investments in their own company’s stock, and then sink the rest into a technology growth fund. I would tell you that it’s not greed that drives us to our lemming like self-destructive behavior.

People jump on such bandwagons, not because they’re greedy, but because they don't want to be left out of what everyone else is doing, and from which many appear to be benefiting. Being left out sucks… big time. We hated being left out in elementary school and high school, and we don't like it any more as adults. No one wants to be the one still looking for an empty chair when the music stops. The feeling of being left out, like greed, is a basic human trait, but it's much more commonly shared than greed. There are unquestionably some among us that are greedy, but none of us relishes the idea of being left out. So, while we do provide the air that inflates our market's bubbles, it's not being driven by all-too-human greed. We are simply trying to ensure that we are not left out of a party to which so many of our peers appear to have been invited. Human traits, such as greed are not things we can change… such traits can only be controlled to varying degree. However, human beings will never like the feeling of being left out… not even for a moment. With all of this in mind, it shouldn't be difficult to imagine how investment bubbles keep happening around the kitchen tables across this country.

"Honey, we should buy more technology stocks… Joe and Mary bought more technology stocks… why can't we buy more technology stocks? Or, more recently: "Honey, we should buy another house… Joe and Mary just bought another house… Tom just bought a place in the desert… everyone but us has at least two houses… shouldn't we buy another house? We don't want to be left out!!" Left Out of a Financially Secure Future During the technology bubble of the last half of the 1990s many of us were contemplating an early retirement as a result of what looked like was newfound investor prowess. Today, we're not entirely sure that we will be able to retire at all, and few of us can remember the name of the last stockbroker we used. Just try mentioning that you received a "tip" from a broker at an upcoming social gathering and you'll quickly see how risk averse we've actually become. Oh sure, we haven't appeared to be all that gun shy these last few years, but that's only because we were floating around in the real estate bubble.

But make no mistake about it… those that jumped into real estate were driven by a need for the assumed relative safety of the real estate market. No one thought investing in real estate could be overly risky because everyone was doing it, and because houses, regardless of their purchase price, could not end up being worth nothing, as was the case for shares of Pets.com and Home Grocer. Those that got into real estate later in the game, however, did so not out of greed… but to ensure that they would not be left out. Numerous studies conducted after the dot-com collapse support this hypothesis. For example, many people reported feeling much less embarrassed about losing money on a popular stock that half the world owns - like AOL or Yahoo - than about losing on an unknown or unpopular stock. As long as everyone's losing… or winning… we're okay with it. This is another example of why we're terrible at investing: We buy what's "hot". All data shows that money flows into high profile mutual funds much faster than the money that flows out of underperforming ones. As a result we continually buy high, and sell low… and it would seem are destined to do so. There are many other aspects of human behavior that impact our ability to invest effectively. Some studies show that we're more scared of losses, than we are happy about gains.

Anchoring is the concept that shows that people tend to place too much credence in recent market events and opinions, and ignore historical, long-term averages and probabilities. And most of us are just generally overconfident. Countless studies show that people generally rate themselves as being above average in their abilities. We often overestimate the precision of our knowledge, and our knowledge relative to others. We're human, and therefore… we're doomed? It would be easy to reach the conclusion that as flawed human beings we are doomed to repeat our failures as far as investing or preparing for our future goes, but I don't believe that has to be true. I believe that, by understanding our inadequacies, we can overcome our established tendencies.

The Solution: Change your view of what you don't want to be left out of… It's time to take hold of the law of nature that dictates that we, as human beings, don't want to feel left out, and harness its power to our advantage. We can learn from the past… if we want to. Consider this: What's the one thing, more than anything else, that you don't want to be left out of: A comfortable retirement, right? Imagine being left out of that. Imagine watching your friends and relatives vacationing together, while you remain at home constrained by a budget far less than you lived with throughout your working life. Perfect. Now that you have the time to travel, you can't afford to. Imagine what it would be like to run out of money long before reaching your life expectancy… your last ten years of life spent struggling to exist below the poverty line. Are you imagining the horror of that situation? Good. Now, compare that with feeling of being left out of buying Cisco Systems at $6 a share, or not buying real estate when everyone else was. If the latter is a pinprick, the former is amputation of both your arms and legs… right? Once you realize that the most important thing not to be left out of is your own comfortable retirement, you can begin to change your perspective on what you need to do differently in order to make sure that you're not.

Savings and Returns on Investments The first step is to save as much as you can, but for the purposes of this article, that's a given. The next step, as any investment advisor will tell you, is to invest those savings, within a certain tolerance for risk, in order to maximize your returns on investment or ROI. That's what we're told, isn't it? If we are to reach our financial goals, it's the long-term performance of our investments that reigns supreme? And it makes sense, on the surface anyway. Of course you should take steps to maximize your ROI, right? If you see one fund doing better than another, it stands to reason that you should put your money where the returns are higher, assuming the risk of doing so is not significantly greater. Doesn't it? I'm not at all sure it does, how about that? In fact, I'm pretty darn sure it's all a pile of crap. ROI is investment advisor horsepucky, nothing more. It’s twaddle, of the highest order. I'm going to tell you something you may not have considered before: Chasing ROI is a fool's errand… a waste of time… essentially, it’s entirely pointless. Why? Why would it not matter what your ROI, or return on investment was?

How can that be? Is that what you're thinking? Because that is what you should be thinking… that's certainly what I would have been thinking before I spent almost all of 2008 intensively studying the markets as related to retirement investing. Now, I'm thinking very differently. ROI doesn't matter for several reasons. The most important one is that your up years don’t really matter nearly as much as you probably think they do. In reality, it's the down years that kill you. If you had invested over the last 25 years in order to earn just a 3-4% annual return every year and never a penny more, but you could skip all of the down years… chances are you'd be a lot better off today. The other reason that attempting to maximize ROI isn't so important is that we are terrible at it. According to John Bogle at Vanguard, between 1980 and 2005, the average annual return was 12.3%, but the average investor earned just 7.3%.

Here we go again… we love to buy high and sell during the fall of ‘08. Consider what Warren Buffet had to say about the last century and the century ahead in his letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders: "Over the last century the Dow went from 66 to 11,497. While this may seem like enormous growth on the surface, compounded annually, it's just 5.3% per year. In this century, if investors matched that return, the Dow would close at 2,000,000 by year end 2099." Two million? The Dow Jones Industrial Average at 2,000,000? I know that's ninety years from now, but still. No one thinks the DOW will ever see two million. The Oracle of Omaha went on to say this: "And anyone who expects to earn 10% annually from equities during this century is implicitly forecasting the Dow to reach 24,000,000 by the year 2100. If your advisor talks to you about such double digit returns from equities going forward, explain this math to him… not that it will faze him. Many helpers are apparently direct descendants of the queen in Alice in Wonderland who said: Why, sometimes I've believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast." Here are the facts about the markets:

- The return on the S&P 500 Index over the last decade was zero… zip… nada.

- Let's say you had retired at the beginning of 2000 when you were 65, and you invested $1,000,000 in the S&P 500 Index on January 1, 2000, and taken withdrawals of just 5% a year, or $50,000, to cover your retirement living expenses. Today, you'd have something in the neighborhood of $300,000 by my calculations… a third of what you started with… and you'd be turning 75 years old.

- Although we enjoyed a bull market that lasted almost 25 years, from 1982-2005, prior to that we languished in a 16 year bear market from 1966 to 1982, during which the stock market's average annual return was -6%... that's negative 6%. And that's according to Art Laffer, the man who's never seen a tax cut he didn't love. (Sorry about that, Art.)

- Diversification is the cornerstone of Modern Portfolio Theory. Diversify your investment holdings, that way if one investment goes south, the others will reduce the impact of the loss. These ideas also appear to make complete sense, but perhaps there's more to the equation than has been explained to us in the past. Maybe conventional wisdom should be questioned. Why should we accept losses at all?

- The biggest threats to your comfortable retirement can be thought of as tax risk, longevity risk, and sequence risk. Tax risk is the risk that taxes will be higher in the future, which will eat into your available income during retirement. Longevity risk is the risk that you'll outlive your money. And sequence risk is the risk of market downturns in the years preceding or immediately following retirement. Taxes… life expectancy… market downturns.

And it’s likely that you’ll never recover… your nest egg will run out before you do just because of one year’s negative returns in the all-powerful stock market. You need to focus on the cash flow your accumulated savings will provide during your retirement years. And not just "maybe” cash flow, but "for sure" cash flow. The kind that used to be called a pension until the Wall Street cabal convinced us, and our government, that the portability of self-directed defined contribution plans was preferable to the stodgy and oh-so-dull defined benefit plans. I saw the movie "Jaws" when I was 12, and as a result was too scared to swim in the ocean until I was 30. I saw the movie "Wall St." when I was almost 30, and as a result I've been losing so much money to land sharks ever since that now I can't even afford to vacation in a locale where I might be eaten by a real shark. It's been a rocky ride, these past 25 years, to say the very least. We've had some good years and some utterly ruinous ones.

And only the eternally disingenuous, self-delusional, and ethically bankrupt pricks who brought us the economic collapse in which we now find ourselves could possibly still have the chutzpah to be perpetuating the idea that the stock market is where we should all be investing our retirement savings. It's beyond being merely bad advice… it’s absolute claptrap. The stock market is equivalent to gambling, pure and simple… except you don't get the free drinks like you do when gambling in Las Vegas. We all need to come to terms with the fact that WE… and by “we” I do mean you… are at best nothing special when it come to investing, and that even though we may have a financial advisor whose personality we may think we like… it's OUR money and OUR job to make sure we don’t lose so much that we don’t reach OUR goals. You might remember the definition of a bull market: A temporary condition that makes investors feel like geniuses. We need to stop listening to smart-sounding drivel from people in snappy suits about the market’s historical average returns, because historically, nobody has ever earned them.

And we better start paying attention to the ubiquitous phrase that follows those historical perspective presentations without fail: "Past performance is no assurance of future results.” I think we should add a few phrases to such disclaimers, like how about: “Returns shown in slide shows are smaller than they appear.” In the U.S. alone there are more than 3.5 trillion books on "how to become a better investor" published each year. That's more than the number published on the subjects of "diet and exercise," and roughly the same number written about Real Estate investing in 2007 that claimed it as eminently safe. Haven't we learned enough by now? Are we simply doomed to continually give back all of our gains and then some every few years until our portfolios would have performed better had they been left inside a SimmonsBeautyrest®? Are we that pie-eyed? Greedy? Short-term memory loss? A learning disability? Restless leg syndrome… what's the deal? We have to have learned better by now, right?

Oh sure… our "light bulb" is on alright… but even with market meltdowns, irrational rallies, Jim Kramer, and unemployment continuing to go in the wrong direction… and now Americans with dollars soon to be used in some countries as memo pads, too many of us are still sitting at home using that light bulb’s glow to read the list of "Hot Stocks for 2010," in Rich & Richer Magazine. Again? Seriously? Look, I'm no financial genius, and at 48 years old I’m not claiming to know everything about retirement. But I'm damn positive about one thing: Running out of money at 83, and living until 93, would be... let's just say "far from ideal" and leave it at that. So, why don't we do something about our situation? Change our ridiculous and irrational behavior. Dump our investment funds that, in truth, we know nothing about, and start saving for our retirement years through vehicles like annuities that offer guarantees that limit our losses in down years, and life insurance policies that can provide us with a source of funds that can be accessed tax-free. Why that's an easy question to answer: We can't... not right now, anyway.

Maybe when the markets come back… don't want to miss the "bounce" don't you know! Well, alrighty then. I guess all I can say is: Hit me. And bring me another one of those cocktails with the little umbrellas in them, would you? Viva Lasfriggen' Vegas, Daddy-O! Oh, and it’s split the sixes, right? Right. Mandelman out. Ergo bibamus.

Martin Andelman is a staff writer for The Niche Report. He also writes an almost daily column on Ml-Implode.com called Mandelman Matters. He also publishes a Monthly Museletter and you can follow "Mandelman" on Twitter. Send your reponses to [email protected].

Martin Andelman is a staff writer for The Niche Report. He also writes an almost daily column on Ml-Implode.com called Mandelman Matters. He also publishes a Monthly Museletter and you can follow "Mandelman" on Twitter. Send your reponses to [email protected].