A risk expert explains why the '10% mark' was a tactical decision by APRA and not just plucked out of thin air.

Working at the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority requires detailed financial knowledge, a head for numbers and, increasingly, a thick skin.

APRA have come under a huge amount of criticism recently, from both mortgage franchises and banks, for their approach to curbing investor lending.

For example, ANZ’s submission to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Home Ownership disputed the dominance of investors outside the metropolitan centres: “Regulators are currently focused on not increasing leverage in the system. [ANZ analysis] shows that outside Melbourne and Sydney, investment activity as a share of total lending remains around 40–42%.”

Looking for an expert view on APRA’s approach, MPA talked to Paul Kennedy, honorary fellow at Macquarie University Applied Finance Centre. With experience in risk management at top banks in Europe and Australia – including CBA and NAB – and time at ASIC, he’s spent years assessing what constitutes ‘risk’, whether investor lending is ‘risky’ as APRA claims, and why the banks don’t seem to agree.

“I think APRA presumably have been a little bit concerned about hot money, and typically the precursor of financial problems has been rapid growth,” Kennedy notes.

“They’re concerned about excessive gearing; they want to ensure people aren’t jumping in on the premise that property rises will move one way and only one way.”

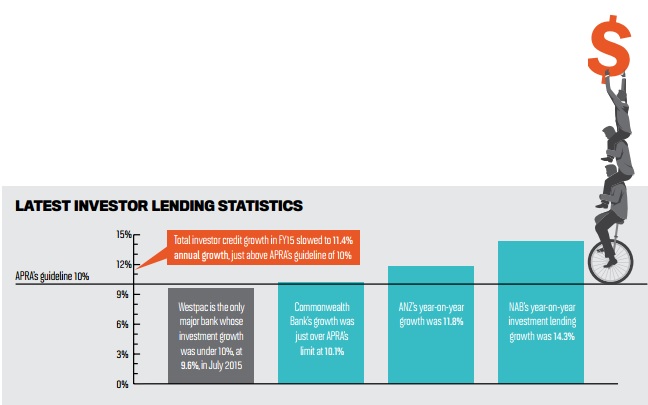

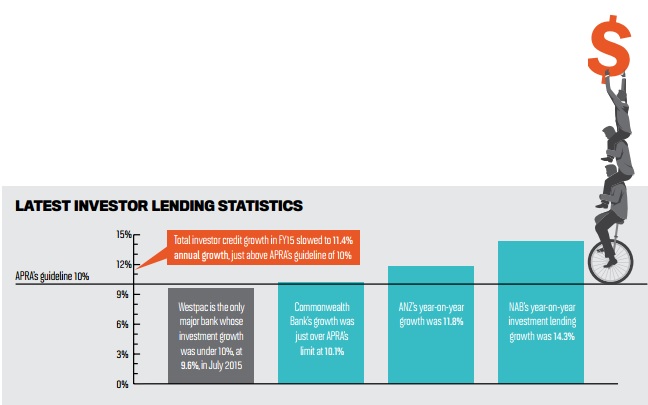

Many brokers see the 10% mark – the limit APRA advises banks to keep investor lending growth below – as picked out of thin air. But Kennedy believes the 10% mark was a tactical decision by APRA. “Ten per cent is around where all the majors are, excluding Macquarie, in terms of growth … it doesn’t feel like a cut; it feels like a break.”

It’s not that APRA are avoiding rocking the boat, Kennedy cautions, but that 10% growth in investment lending is the limit of APRA’s appetite, which in turn is based on historic data. Crucially, this data differs from what the banks see: “APRA has access to all of the banks’ information; it’s more of a difference in perspective."

“Banks absolutely manage risk,” Kennedy adds. “The idea that they’re entirely revenuedriven and don’t think of the future is completely incorrect. What APRA is doing, he argues, is accelerating a change in perception towards investor lending that would have happened anyway. “The challenge is deciding when it’s time to turn the dials, and APRA wants to ensure that question can’t be fudged or deferred too long – that banks act on the information they receive.”

Increasingly bank regulation is doing the job the RBA used to do in managing the economy, Kennedy believes. He thinks we’ll see more use of fine-tuning, such as countries like China already regularly use, as interest-rate changes become less effective in managing the economy. The danger is in APRA going too far, he concludes. “The more intrusive and more interventionist the regulator is, the more they risk insourcing risk management to themselves and not encouraging the banks to develop their own risk management … they must not become accountable for everything.

APRA have come under a huge amount of criticism recently, from both mortgage franchises and banks, for their approach to curbing investor lending.

For example, ANZ’s submission to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Home Ownership disputed the dominance of investors outside the metropolitan centres: “Regulators are currently focused on not increasing leverage in the system. [ANZ analysis] shows that outside Melbourne and Sydney, investment activity as a share of total lending remains around 40–42%.”

Looking for an expert view on APRA’s approach, MPA talked to Paul Kennedy, honorary fellow at Macquarie University Applied Finance Centre. With experience in risk management at top banks in Europe and Australia – including CBA and NAB – and time at ASIC, he’s spent years assessing what constitutes ‘risk’, whether investor lending is ‘risky’ as APRA claims, and why the banks don’t seem to agree.

“I think APRA presumably have been a little bit concerned about hot money, and typically the precursor of financial problems has been rapid growth,” Kennedy notes.

“They’re concerned about excessive gearing; they want to ensure people aren’t jumping in on the premise that property rises will move one way and only one way.”

Many brokers see the 10% mark – the limit APRA advises banks to keep investor lending growth below – as picked out of thin air. But Kennedy believes the 10% mark was a tactical decision by APRA. “Ten per cent is around where all the majors are, excluding Macquarie, in terms of growth … it doesn’t feel like a cut; it feels like a break.”

It’s not that APRA are avoiding rocking the boat, Kennedy cautions, but that 10% growth in investment lending is the limit of APRA’s appetite, which in turn is based on historic data. Crucially, this data differs from what the banks see: “APRA has access to all of the banks’ information; it’s more of a difference in perspective."

“Banks absolutely manage risk,” Kennedy adds. “The idea that they’re entirely revenuedriven and don’t think of the future is completely incorrect. What APRA is doing, he argues, is accelerating a change in perception towards investor lending that would have happened anyway. “The challenge is deciding when it’s time to turn the dials, and APRA wants to ensure that question can’t be fudged or deferred too long – that banks act on the information they receive.”

Increasingly bank regulation is doing the job the RBA used to do in managing the economy, Kennedy believes. He thinks we’ll see more use of fine-tuning, such as countries like China already regularly use, as interest-rate changes become less effective in managing the economy. The danger is in APRA going too far, he concludes. “The more intrusive and more interventionist the regulator is, the more they risk insourcing risk management to themselves and not encouraging the banks to develop their own risk management … they must not become accountable for everything.